No True Science

Why the Twenty-First Century Feels like the Seventeenth

I’m not a particular fan of vampire movies. My youthful enthusiasm for the Hammer horror films of Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing had long since receded by the time the Twilight trilogy and other twenty-first century variations on the bloodsucker genre came along. Nevertheless, I do appreciate the Gothic. I once spent a fabulously atmospheric evening in an old monastery-cum-guest house in Cuenca, curled up in bed reading Matthew Lewis’s torrid eighteenth century melodrama The Monk - call it method reading.

Lewis’ mad novel was one of the building blocks of the Gothic tradition that includes Frankenstein, Dracula, The Mysteries of Udolpho, Jan Potocki’s The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella Carmilla, Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories, the paintings of Goya and Henry Fuseli, Hammer horror films, Black Sabbath’s album covers and Ann Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. The trailer of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu remake enticed me to the cinema for the first time in 2025, because it seemed to have all the essential elements of the Gothic genre stamped all over it.

The film didn’t disappoint. Mannered histrionic acting; Tim Burtonesque hyper-real fairy tale sets; a hulking blood-drinking demon speaking ‘ancient Dacian’ in a voice to peel the paint off walls; driverless carriages on lonely roads; wild-eyed superstitious villagers; a pervasive atmosphere of dread and an imperilled heroine whose body becomes the battleground between good and evil - Nosferatu is the full Gothic. It gleefully recaptures the somnambulistic nightmarish quality of Murnau’s 1922 original, and (this is the twenty-first century after all), ramps up the already-overwrought sexual hysteria and melodrama of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, while thankfully leaving aside the antisemitic tropes that featured in both Stoker’s novel and the movie that it pays homage to.

Eggers’ vampire-demon, the Count of Orlok, emanates from some dark, almost primeval corner of Eastern Europe, but he also inhabits a non-spatial fifth dimension and sends telepathic messages of dominance and submission that penetrate the dreams of his victims and servants long before he sees them.

Like so many of its predecessors, it is barking nonsense, which requires a complete suspension of disbelief to accept even its basic premises. But the fascination of the Gothic has never been due to the genre’s socioeconomic precision or plausible plotlines. It’s not for nothing that the golden age of the genre coincided with the highwatermark of the scientific revolution at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries.

This was an era in which, as the Encyclopedia Britannica puts it, ‘the use and celebration of reason, the power by which humans understand the universe and improve their own condition,’ were central to Enlightenment thought, and ‘The goals of rational humanity were considered to be knowledge, freedom, and happiness.’

Practitioners of the Gothic took a different view. They dwelt in the shadows not the light. In their stories and visions, reason struggles to prevail against darker human instincts and more powerful forces emanating from beyond the human.

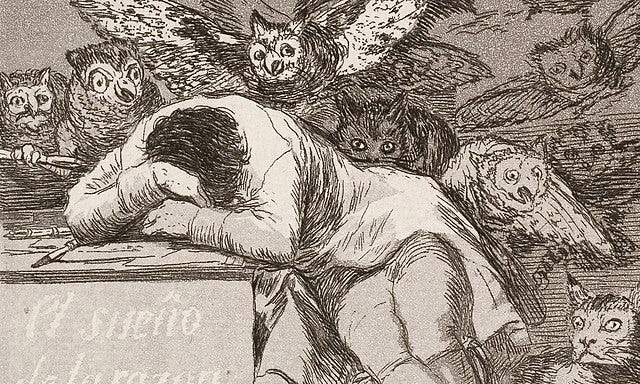

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a scientist’s quest for knowledge for its own sake - the quintessential Enlightenment pursuit - leads him to create a monster that destroys him and everyone he loves. Matthew Lewis’s monk rapes his drugged lover in a crypt, murders her mother, dabbles in sorcery and then sells his soul to the devil. Goya’s sleeping writer falls into daydreams inhabited by freakish starey-eyed birds and monstrous apparitions. And Dracula exerts a mesmerising seductive power over women who are half-complicit in their own downfall. It’s not exactly a blueprint for a better world.

If the Gothic was the dark side of romanticism, it also hearkened back to a pre-Enlightenment era in which ‘the use and celebration of reason’ was not the dominant ethos in society, when was entirely normal to believe in demons that feasted on human blood, in witches’ spells that caused crops to fail, the deaths of children, and other tragedies and calamities.

Witchcraft was only one of many superstitions that Enlightenment scholars and their descendants believed would gradually disappear through the diffusion of scientific knowledge and education. Gothic writers and artists saw things differently. They may not have been psychoanalysts, but they recognized, as psychoanalysis later did, that goodness and virtue did not necessarily come naturally, and that there were elements within the human psyche that could not easily be removed through reason and scientific advancement.

The Enlightenment is often imagined as a kind of universal threshold - an unstoppable process that transformed humanity’s view of itself and of nature forever. Nosferatu refers to these assumptions. When the disgraced occultist Von Franz is challenged by a nineteenth century medical doctor about his belief in ‘medievial devilry’, he replies:

I have seen things in this world that would have made Isaac Newton crawl back into his mother’s womb. We have not become so enlightened as we have been blinded by the gaseous light of science. I have wrestled with the Devil as Jacob wrestled the angel in Peniel and I tell you, if we are to tame darkness, we must first face that it exists. Meine Herren, we are here encountering the undead plague carrier…the Vampyr…Nosferatu.

In an age of artificial intelligence, tech-driven information, mobile phones, satellites, and unmanned aerial vehicles, and a thousand other technological achievements that were made possible through science, reason, and empirical inquiry, Von Franz’s words ought to seem as quaint and anachronistic to us as they do to his astounded listeners. And yet we live in a century in which millions of QAnon conspiracists believe that Satan-worshipping celebrities are murdering children in order to harvest adrenochrome from their brains and attain eternal youth.

One of these believers shot up a pizza parlour in Washington in order to rescue children from a basement - a dim and foolhardy act of altruism that only came to an end when he found that there were no children and no basement. In December 2020, a former information consultant named Anthony Quinn Warner died in the explosion that he set off outside the AT&T building in Nashville. According to NBC, Warner may have subscribed to an internet conspiracy in which

politicians and other prominent people, including the Clintons and the comedian Bob Hope, who died in 2003, are actually lizard-like creatures sent to Earth and are responsible for a number of historic tragedies. Justin Bieber and the Obamas have also been named in the conspiracy theory.

Put these ingredients together and vampires don’t seem that outlandish. According to a 2021 YouGov poll, only thirteen percent of Americans believe that vampires are real, but forty-three percent believe that demons exist. As Leonardo da Vinci might have said, this is not true science. It was only last year that the ridiculous white supremacist fraud Tucker Carlson claimed to have found bite marks on his body, supposedly inflicted on him by a demon while his wife was sleeping.

Even if Carlson didn’t believe that this really happened, you can bet that many people did. And as easy as it is to mock this dizzy crackpotism, it’s worth remembering that it can have real-world consequences. Because if you can believe that demons gnaw on tv presenters, or that Tom Hanks and Ellen DeGeneres are cannibals, you won’t have much trouble accepting, for example, that the Democrats fixed the 2020 election, that liberals are trying to ‘replace’ the white race, or that ‘15-minute cities’ are intended to strip you of your material goods and trap you in a ghetto.

Nazism exploited a similar credulity, and propagated its own conspiracies and occult obsessions, whether pursuing crazed racial origins theories in the Arctic or the Pyrenees, or fusing medieval blood libel fantasies of Jews drinking children’s blood into twentieth century imagery of the vampiric Jew.

QAnon’s X-File pop culture kitsch has echoes of this same tradition; its cannibal elite conspiracies exploit real-world distrust of governments and institutions in order to create an epistemological crazytown in which anything that can be believed, will be believed, and spread through a culture that too often prioritises entertaining fantasies over knowledge and critical thinking.

These tendencies were often morbidly present during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Where uneducated seventeenth century peasants once believed that harmless widows and single women from their village were cavorting with Satan in order to make them ill or cause their crops to wilt, millions of people in Europe and America came to believe that COVID-19 was spread by mobile phone antennae. The fact that most of these people had been to school and may even have been to university did not prevent them from believing that global ‘elites’ had deliberately spread COVID-19 through 5G electromagnetic rays.

A 2021 survey of ‘radiophobic’ COVID-19 conspiracy theories, found theories that extended across a broad spectrum. Some of their believers thought that 5G weakens the immune system; others thought that it infected people directly, or caused symptoms that simulate viral infection. And there were also those who believed that before COVID-19, mobile towers caused SARS, and 4G Swine Flu. The survey’s authors noted that

In all iterations, 5G is depicted as either “Satan’s strategy” to advance the apocalypse, or the work of a techno-capitalist government cabal that seeks to reduce the population, profit from a vaccine, or embed micro-chips into the vaccine for the purposes of surveillance or control.

This is not quite naked witches flying off on broomsticks to cavort with the horned beast, but it is not the most plausible explanation of how viruses are passed from human to human. In the twenty-first century, as in the seventeenth, malign conspiracies explain natural tragedies and calamities, but now technology, science and medicine, rather than the natural world, are depicted as expressions of dark magic, operated by shadowy malign forces, in which viruses can be spread through mobile electromagnetic frequencies, and vaccines plant micro-chips in the brain and body..

Even in our age of cities, machines and material comforts, such conspiracies can be more comforting and appealing than the recognition that human beings remain vulnerable organisms that are as susceptible to viruses and infections as we have always been. Yet ask Google ‘did Satan cause the COVID-19 virus’ and you will find yourself exposed to ideas and debates that would not have seemed entirely unfamiliar to the witchfinder generals, lawyers and inquisitors of the seventeenth century.

Some Christians are unsure whether Covid-19 is the work of God or the work of Satan, or whether the Pandemic was in fact God’s ‘judgment against humanity’. Others, such as the South African Chief Justice, wonder whether the COVID-19 vaccine was intended to ‘advance a Satanic agenda of the mark of the beast.’

Despite - and to some extent because of - the technological progress we have made, the inhabitants of our media-saturated world often appear strikingly amenable to pseudo-explanations that Voltaire and Diderot would have scorned. This willingness is even more striking and anomalous now that it was in the past, because there are more scientific explanations available for the processes that these theories supposedly describe, and such information is more readily available.

But the extraordinary popular delusions and madness of twenty-first century digital crowds are as impervious to reason as those of their predecessors. In our anxious times, whole swathes of the population appear willing to suspend disbelief and accept explanations and theories that make no sense, that solve nothing, and cure nothing, and many seem to prefer to do this, rather than engage with informed knowledge and expertise.

There is a grim irony that this collective descent into stupidity and superstition should be taking place at precisely the point when artificial intelligence is poised to undermine humanity’s ability to think for itself. Because the world is not a vampire movie or a Netflix series. No demons or monsters - no matter how vividly and compellingly imagined - can match the banal malevolence of our contemporary monsters, snake oil salesmen, megalomaniacs and would-be dictators who infest our rotten politics and decaying societies.

It may be comforting to believe that plagues are caused by electromagnetic rays, and that the powerful drink the blood of children. But none of this will help prevent the next pandemic. Fantasies about satanic cabals and red pills will not shed any light on the actual structures and forces that are draining democracies across the world of their ability to make the world a better place, or ensure our collective survival.

These forces are far more threatening than anything in Nosferatu. They cannot be vanquished by exposure to daylight or a stake in the heart, but only through the more complex task of building a future that reflects our best dreams, ideas and aspirations, rather than our nightmares.

Great stuff Matt