The Settlers

A Daring Reflection on Colonial Genocide

I’m currently writing a book about the conquest of Patagonia, and some readers may remember, I was lucky enough to go there last year as part of my research last year. I’ve spent most my time since then reading and writing about the issues that I looked at during that journey. So naturally, I was very keen to see the film Los Colonos (The Settlers), by the Chilean director Felipe Gálvez Haberle, which is set in some of the places that I visited and deals with some of the themes in my book.

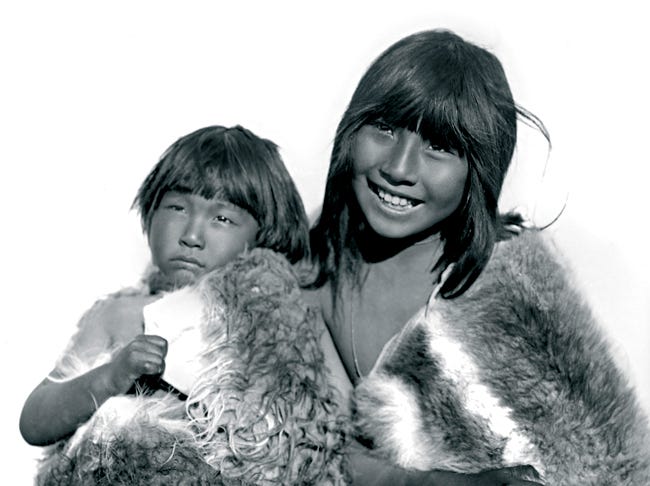

For those who don’t know, Gálvez’s film deals with the genocide of the Selk’nam or Ona people, who lived in the north of the Isla Grande (Big Island) of Tierra del Fuego. Unlike the Yámana or Yahgan ‘canoe Indians’, the Selk’nam were ‘foot Indians’, who lived in the grassy hills and plains north of the Sierra de Alvear on Isla Grande that they called karakinká - our land.

Separated from the South American mainland by the Strait of Magellan, Selk’nam tribes had inhabited these lands for some 9,000 years, living off the guanaco (a camelid species similar to lamas) herds that provided their main source of food and clothing.

The Selk’nam hunted guanaco on foot, using bows and arrows to wound or kill them and dogs to run them down. All this came to an end from the 1880s to the first decades of the twentieth century, when the colonization processes that were taking place elsewhere in southern Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego reached the Selk’nam, and all but wiped them out.

Until then, the Selk’nam had rarely seen white men. Unlike the Yahgan or Kawésqar ‘canoe Indians’ who inhabited the islands and coasts further south, they had very little contact with Europeans until the 1880s, when alluvial gold deposits were discovered on the coasts of Isla Grande, the Strait of Magellan and the surrounding islands. The ‘Patagonian gold rush’ brought miners and prospectors to Isla Grande for the first time. Selk’nam sometimes attacked miners who they saw as intruders and competitors for food, and miners sometimes kidnapped Selk’nam as sexual slaves.

Military/scientific expeditions began to explore the island in this period, and these encounters also turned to armed confrontation. In 1886, the Romanian adventurer Julius Popper explored Tierra del Fuego on behalf of the Argentinian government. Popper took various photographs of the expedition, including this infamous picture of the aftermath of a ‘battle’:

But the real calamity for the Selk’nam people was the advent of the sheep-farming economy. From 1874 onwards the Chilean government began to lease large tracts of land to Chilean and foreign nationals who were willing to use them to churn out wool and mutton for mostly European markets. In theory, these concessions imposed limits on how much land you could own, but in practice these limitations were overcome by big landowners, using their political contacts in the local and regional governments.

This was the period in which men like José Menéndez, Mauricio Braun, and Rudolf Stubenrauch amassed vast wealth, and the Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego (The Tierra del Fuego Exploitation Society), took over most of Isla Grande to become the biggest sheep-farming corporation in the world by 1930.

Genocide

All this was a disaster for the Selk’nam. Their lands were fenced off, depriving them of access to the sea, and driving away the guanaco herds on which they depended. Devoid of any sense of private property, they began hunting the animal they called the ‘white guanaco’ to compensate, and the ranchers and landowners responded with extreme violence. Unlike the conquest of northern Patagonia, which was primarily a military enterprise, the elimination of the Selk’nam was mostly privatised, paramilitary violence, carried out by hired gangs, peons and estate workers, who massacred and killed Selk’nam for their employers, and often provided body parts to prove each kill.

Many of them were foreign. One of the most notorious ‘Indian hunters’ of the period was Alexander MacLennan, a Scottish veteran of Kitchener’s army in Sudan, who the Selk’nam called the ‘chancho colorado’ (red pig), because of his reddish hair and beard. In Lucas Bridges’ classic memoir Uttermost Part of the Earth, MacClennan appears as ‘McInch’ to avoid libel, and Bridges describes the ‘uncrowned king of Rio Grande’ as ‘a most curious mixture. He who took open pride in having persecuted and murdered the Indians - albeit for their own good - hated to see a sore-necked yoke-ox, or a horse being unduly spurred.’

There were many MacLennans on Isla Grande, who regarded the Selk’nam as vermin and shot them on sight, or left sheep poisoned with strychnine for hungry Selk’nam to eat. Eventually, the landowners reached an agreement with the Salesian order to deport Selk’nam to the Salesian mission on Dawson Island - the site of one of Pinochet’s future concentration camps - where they died in droves from measles, tuberculosis, smallpox and syphilis.

By the 1920s, a people that had numbered between 3,000-4,000 in the 1880s had been reduced to less than a hundred. The Selk’nam stood in the way of an economic model, financed by national and international capital and directed towards foreign markets, that saw Patagonia’s ‘empty’ lands purely as pasture for sheep and cattle.

Until relatively recently, the horrific consequences of that model received little public acknowledgement. It was not until 2008, that Chile’s Comisión Verdad Histórico y Nuevo Trato con los Pueblos Indígenas (Commission on Historical Truth and New Deal with Indigenous Peoples) described the destruction of the Aonikenk, the Selk’nam, the Kawésqar and Yahgan as a ‘great tragedy. The greatest committed against the Indigenous peoples in Chilean territory.’ The Commission declared unequivocally that ‘ It was a process of extermination that took place. It was a genocide.’

The ‘genocide of the Selk’nam’ was the title of the sculptor Richard Yasic Israel’s epic mural in Porvenir on Isla Grande, which I saw last year:

And it’s also the subject of Gálvez’s brutal and uncompromising film. There are real historical characters here: Alexander MacLennan and José Menéndez are central protagonists. Even the legendary Argentinian scientist, explorer, and obsessive collector of indigenous skulls, Francisco ‘Perito’ Moreno makes an appearance.

But Los Colonos is not a documentary rendition of any particular event, but a personal reflection on colonization in general, and the genocidal colonization of the Chilean south in particular. It asks its (Chilean) audience to see how the violence it depicts was both central to the history of the nation, and also how it has been erased from that history.

On the surface, the ‘plot’ is a conventional Western device: hard men sent on a violent journey, in a harsh, unforgiving landscape that is also breathtakingly beautiful. Anyone who has ever been to Patagonia will swoon at the way the Gálvez’s cinematographer Simone D'Arcangelo has rendered the wild desolation of northern Tierra del Fuego.

From the opening sequence, the film has a stark, ominous intensity, as Menéndez sends his murderous lackey MacLennan - still wearing his British army uniform - to clear Tierra del Fuego of Indians from the Strait of Magellan to the Atlantic. The trailer gives you the flavour:

We’ve seen something like this before, in The Searchers or The Unforgiven, in Cormac McCarthy novels. MacLennan is accompanied by an American bounty-hunter named Bill, who can ‘smell an Indian from ten miles away.’ And the third member of the party is Segundo, a mestizo (mixed race) peon from the island of Chiloé, chosen for his marksmanship.

Segundo is a reluctant participant in this exterminatory journey. And even though he rarely speaks, the camera frequently registers his anger, horror and disgust at his two companions, both of whom treat him with casual racism. Segundo, like the other indigenous characters in the film who have become part of white society, reminds me of the Incas who accompany the Spanish conquistadores in Herzog’s Aguirre, Wrath of God.

In both films, the ‘Indians’ are prisoners of colonial society, whose survival depends on doing what they are told and never questioning or challenging anything. Even when they are protagonists in the vicious enterprises they have been forced into, they are also observers, who exude unexpressed trauma and profound melancholy.

Segundo is accused by his companions of ‘dual loyalties’, and it’s clear that he is sickened by what he is being asked to do. I won’t say what that is. Suffice to say that the violence is as brutal as it needs to be, but no more than that. Compared to Sam Peckinpah or Clint Eastwood, it’s almost restrained.

MacLennan’s journey takes him to places that he didn’t expect, including a terrifying encounter with a psychopathic Kurtz-like English army colonel who doesn’t appear in any historical record of the period. But Segundo meets a Selk’nam woman named Kiepja - a little homage to the Selk’nam shaman Lola Kiepja (1874-1966), who the American anthropologist Anne Chapman once described as the ‘last Selk’nam.

And at this point, about three quarters of the way through the film, Gálvez does something no director of Westerns would do: he suddenly abandons the characters, the landscape and the exterminatory journey, and takes us to José Menéndez’s palace in Punta Arenas, seven years later.

Menéndez and his wife are receiving an envoy of the Chilean president, named Marcial Vicuña, who has come to the south, supposedly to investigate some of the crimes against the Selk’nam for which MacLennan - and Menéndez were responsible.

For a few moments, you’re allowed to believe that the Chilean government really did seek justice for the Selk’nam, even if that meant challenging the all-powerful ‘king of Patagonia.’ Menéndez and his wife believe it, and launch into a spirited a defence of their actions. But Vicuña has other intentions. He’s there to show the public that the government cares about mass murder, but not to actually do anything about it or seek redress. As far as I know, nothing like this ever happened, apart from the 1895 judicial investigation into the vejamenes - abuses - against the Selk’nam, ordered by the Chilean government, which came to nothing and found no one guilty of anything.

But Gálvez’s point is well-made, and it’s rammed home further in a brilliant sequence in which Vicuña visits Segundo and Kiepja (now named Rosa) who are living by the sea in Chiloé. Accompanied by two policemen, Vicuña tells Segundo that he is seeking justice for MacLennan’s crimes, and then forces Segundo and Rosa to drink tea, wearing ‘civilized’ clothes, so that he can film them.

Kiepja refuses to play the part of ‘Rosa’, and disobeys Vicuña’s order to ‘drink tea’. The last shot of her angry, defiant face reminded me of the photographs taken by the French army of ‘unveiled’ women in Algeria during the Algerian war. This, Gálvez suggests, is the colonial masquerade that Chile remembers. As the credits roll, old film sequences show immigrants arriving in Chile, trains and boats, and all the trappings of modernity. It’s a long way from the brooding ‘bloodlands’ of Tierra del Fuego, and a bold invitation to Chile to rethink how it got to be the way it is, and what the ‘conquest’ of Tierra del Fuego really entailed.

Of course Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia aren’t the only places where these processes unfolded, and this why, in the 21st century, the fate of the world’s indigenous peoples under colonialism remains a searing political issue. And this brilliant film/essay is part of that re-examination, and a powerful reminder of Walter Benjamin’s observation that ‘there is no document of civilization that is not also a record of barbarism.’

A heartbreaking but powerfully told story, Matt.

What a sad and dispiriting tale. Thank you for sharing it Matt. Not sure I can face the film.