On July 24, 1914, Count Harry Kessler, the ubiquitous Anglo-German chronicler of the Belle Epoque wrote in his voluminous diary: ‘In the evening dined with Caillon. Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia has created a serious situation in the East.’ The next day Kessler recorded that ‘The situation in the east has suddenly become very serious.’

Two days later, ‘very serious’ had become ‘very bad news. Austria is supposed to have declared war on Serbia’. That evening Kessler told his French innkeeper that war had been declared, to which she responded, ‘Ah? We are not paying attention, monsieur’, and ‘continued tranquilly her work.’

Kessler wasn’t entirely distressed by this news. For all his cosmopolitanism, he had strong nationalist inclinations. ‘There is no more hollow Utopia than eternal Peace, and a mischievous one into the bargain,’ he told his sister in 1911, during the episode known to history as the Second Moroccan Crisis, ‘All nations have become what they are by war, and I shouldn’t give two pence for a world in which the possibility of war was abolished.’

Kessler quickly lost some of that enthusiasm, on witnessing the unparalleled slaughter of twentieth century technological warfare. But initially, he responded to the ‘serious situation in the East’ with a mixture of concern, resignation and foreboding that will be familiar to many people who have heard rumours of war filtering in from faraway. Because whether we support them or not, wars usually begin with crises and events unfolding a long way from our daily lives, whose outcome is decided by groups of powerful men who bring war to us regardless of whether we want it or not.

In Kessler’s time, World War I was decided by kings, diplomats, spies, and generals, and vain, fatuous, ridiculous men like the German Kaiser and the ancient Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz-Joseph. War was not a surprise. It was the logical outcome of nationalist and imperial conflicts; of an arms race in which each side tried to keep up or outdo the other; by military plans worked over a thousand times till they became automatic; by a system of interlocking national alliances that turned every geopolitical crisis into a potential geopolitical flashpoint, and finally triggered a cascade of mobilisations in which each side acted in support of their allies.

Israel and Iran: Playing Chicken

This was how it was then, and some of it is true today. On Sunday morning, I woke up to find that Iran had launched a drone attack on Israel. This wasn’t entirely surprising: ever since Israel attacked the Iranian embassy in Damascus at the beginning of month, Iran had promised some form of retaliation.

Western leaders instantly accused Iran of ‘recklessness’, which is true, though it raises the question of why these same leaders did not condemn Israel for recklessness - or for anything at all - when it violated diplomatic norms and bombed an embassy.

This was the first time that Iran has directly attacked Israel, and its 300-strong drone assault was easily-repelled, as Iran undoubtedly knew it would be, which is why it flagged up the operation beforehand. Whatever the language that its leaders use, Iran is not in a position to fight an all-out war with Israel, let alone with Israel and the United States. On Sunday Iran’s UN Mission said that ‘The matter can be deemed concluded,’ which suggests that it was intended as a face-saving, rabble-rousing response to Israel’s attack on its embassy.

So this geopolitical-military theatre is good news, within a very narrow definition of ‘good.’ The other good news is that Biden has reportedly warned Netanyahu not to launch a counterattack.

Lucky world. Because luck, rather than wisdom or judgement, is pretty much the only thing preventing a war that could be decided at any moment either by a government engaging in genocidal violence in Gaza, or by a tyranny that shoots down schoolgirls who don’t want to wear the hijab.

Nor should we take much consolation from the ineffectual attempts of a decaying superpower to impose a ‘rules-based framework’ on a chaotic world that is no longer as ‘unipolar’ as it once seemed to be. In geopolitical time, it seems like aeons have passed since George Bush hailed the anti-Iraq coalition as the beginning of a New World Order in the lead-up to the first Gulf War. It’s not much more than a decade since Pentagon-affiliated military thinktanks were still imagining that the US would become the policeman of globalisation and dominate the ‘global battlespace’ through its unrivalled technological reach and its arsenal of sci-if weaponry.

Those aspirations also belong to another era. Now the US has turned out to be as fragile and prone to implosion as the world it once set out to save, and even Iran and the Houthis can wage warfare-by-drone. And if US military technology can still fend them off, its military power does not translate into with strategic dominance. Even Biden’s ‘bear-hugging’ of Netanyahu has turned out to be a mutual death-embrace, as Netanyahu drags the US towards an all-out war that it doesn’t want, while Biden struggles to distance itself from the mass slaughter in Gaza in which babies are now starving to death.

Biden may have told Netanyahu not to retaliate, but that decision will be taken by the most dangerous, fanatical and reckless government in Israeli history, regardless of what Biden wants.

Netanyahu knows that a wider conflict is probably the only thing that can save his political skin, and he also knows that if Israel does retaliate to Iran’s retaliation, in Lebanon or Syria or directly, through missile strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, the US will take Israel’s side. A regional war might or might not solve Netanyahu’s political problems, but it would kill tens of thousands of people, and usher in a cascade of events that no one can control. This will not bother Netanyahu, and there are others, like him who long for this outcome.

No one will be surprised to find former British army colonel Richard Kemp amongst them. Last week in the Telegraph, Kemp was arguing that ‘the UK should be ready to take direct military action against Iran’ in the event of an Iranian attack on Israel, and that Israel should retaliate on the territory of the attacker’, because ‘Timidity and restraint may feel more comfortable in the short term but failure to meet violence with even greater violence always encourages the aggressor.’

Iran could argue exactly the same thing, in regard to the attack on its embassy or Israeli drone attacks on its own territory earlier this year. But for Kemp, and for so many others, only one state has the right to ‘retaliate’ whenever and however it chooses, and it is never the aggressor.

For those of us who don’t accept these premises, both Israel’s attack on Damascus and Iran’s drone attacks are a game of chicken, played with matches in a hay barn. At present, Europe and the West are fighting a proxy war in Ukraine with Russia, which is receiving military technology and intelligence information from China. Russia is an Iranian ally, and China is also developing closer relations with Iran.

If the West took Israel’s side in a war with Iran, such a confrontation could easily spread beyond the Middle East. You don’t have to respect the Iranian regime to oppose a war that would bring death and destruction to tens and thousands of Iranians. You don’t have to admire the Chinese political system to observe that the ‘threat’ China poses to the US and the West derives primarily from its economic, rather than military power - and which is also exacerbated by the West’s declining global economic power.

You can support Ukraine’s right to self-determination, while also noting that Western states have been far more militaristic since the end of the Cold War than either Russia or Iran. You can also condemn the diplomatic idiocy and arrogance that Europe and the US showed for so many years, in marginalising, humiliating and cornering a country with a long tradition of paranoid chauvinism, to the point when the gangster-spy in the Kremlin could present his invasion - however dishonestly - as an act of self-defence.

The ‘1938 Moment’

And support for Ukraine does not mean that you have to accept that Britain is facing a ‘1938 moment’, as the head of the British Army, General Patrick Sanders, suggested in January this year.

According to Sanders, national mobilisation may be required so that the ‘prewar generation’ can fight Russia as a ‘whole-of-nation undertaking’. The security thinktank Chatham House has also called for re-armament in order to address ‘not only short-term threats posed by the likes of Russia, but also the medium-term challenge of China.’

Other defence pundits have called for the military budget to be raised to 2.5 percent. Naturally the Labour Party has promised to do this. Because even in a country where schoolchildren are not being fed and you are lucky to be able to get a hospital appointment, war and the preparation for war will always take precedence and a budget will always be found for it.

As always, these preparations tend to be couched in moralistic talk about freedom, democracy, and Western values. We should not be fooled. In the 21st century’s terror wars, the world’s only superpower spent trillions on a succession of destructive and failed wars while China has achieved its global position without firing a shot.

Think what you like about Chinese authoritarianism, but China’s power derives not from its military arsenal, but from its successful participation in the international trading system. Yet now - in part because of that - China has joined the list of military threats and ‘challenges’ to the West, along with the blundering tyrant Putin.

And beyond the war with Russia that we must prepare for, military thinktanks in the US are also factoring in the possibility of a war with China in the ‘2025-32 time frame. Meanwhile China, according to the Foreign Policy journal, ‘is amassing ships, planes, and missiles as part of the largest military buildup by any country in decades’, in order to prepare for ‘worst-case and extreme scenarios.’

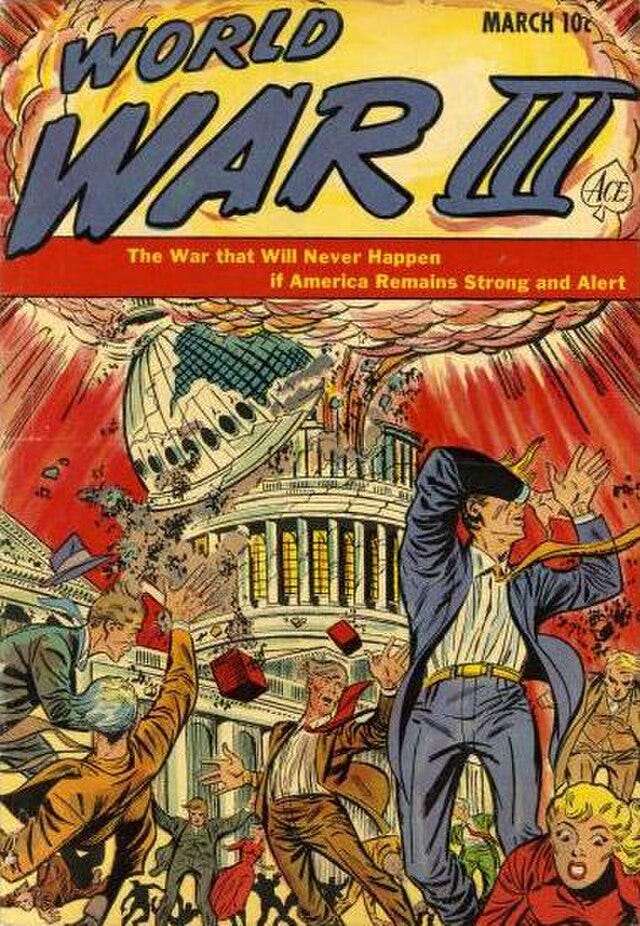

These are frightening possibilities, but we cannot dismiss them, because nowadays, as Bob Dylan once sang in Talkin’ World War III Blues, everybody’s been dreaming these dreams, and few, if any world leaders, appear to have the will or the judgement to avoid a calamity even when they see one coming.

In a world that seethes with rancid dreams of national greatness, where states increasingly behave like playground gangs, the worst possible outcome remains a possibility. In the US, voters face the choice between two old men in their eighties, one of whom is a corrupt criminal and incipient fascist, and the other a democrat who has folded his arms in the face of mass slaughter, and given the perpetrator the weapons to do it.

In these circumstances, war can seem to be a distraction from domestic chaos and division, and a means of imposing social discipline and national unity in the name of ‘moral clarity.’

This a dangerous luxury we can’t afford.

Harry Kessler may once have spurned a ‘utopian’ without war, but we need, more than ever, to be utopian, and to seek ways of ending conflicts rather than extending them. Right now, millions of people in the Horn of Africa are facing the worst drought in 40 years. Drought is also spreading across sub-Saharan Africa. Climate change can’t easily be parsed into rearmament and military preparedness, but it poses more of a threat to the West - and to humanity - than China, Iran, or even Russia.

A global conflict would end any possibility of being able to take action on this or any other collective problem. So when we look at the succession of crises unfolding across the world, we should not allow ourselves to be deceived by vapid rhetoric about morality and values, or by the cynical pessimism underpinning the ‘realist’ conception of international relations.

We should not allow the pundits of the Daily Mail to lull us into ‘rearmament.’ We should not allow generals and politicians to turn another generation into the ‘pre-war generation.’

Our children and grandchildren are not cannon fodder and food for drones. War is not inevitable. It is nearly always a choice, and we should not be conned into thinking otherwise.

We should not be seduced into another futile conflict by the fatuous, ridiculous leaders of our era. Otherwise we may one day find ourselves, like Harry Kessler, reading the bad news over breakfast, or sitting, like WH Auden in 1939, in a dive on Fifty-Second Street, uncertain and afraid, and looking back on our own low, dishonest decade(s), knowing that the machine has been started and cannot be turned off.