On Heroes and Tombs

Argentina's Statue Wars and the Battle for History

Not many non-Argentinians will be familiar with the little town of Choele-Choel, on the River Negro. Apart from a camping site and sports ground on the island in the middle of the river, there’s no particular reason to visit this dusty little provincial town about a thousand kilometres from Buenos Aires. I was there last month, and the main reason for my visit was the imposing tower that stands on a hill overlooking the highway just beyond Choele-Choel, with a red streak pouring down its facade like blood from a wound.

The monolith is a monument to the 1879 ‘Conquest of the Desert’, and it was erected in the spot where the then-Minister of War General Julio Argentino Roca arrived with the Argentine army on May 25 that year.

Until that day, Choele Choel was regarded as the ‘bandit capital’ of Indian Argentina. It was here that Mapuche and other indigenous peoples who inhabited northern Patagonia and the southern pampas of Buenos Aires brought captives, cattle and horses taken during ‘malones’ - raids - on white settlements.

Because of its location about half-way between the Atlantic and the confluence of the Nuequen and Limay rivers, Choele-Choel was an important waystation on the ‘rastrilladas’ - trails - that connected Argentina and Chile. On a good day, thousands of cattle and horses might be rounded up on the island, waiting to be sold on in Chile.

In breaching an Indian ‘fortress’ that was previously regarded as unassailable, the arrival of Roca’s armies marked the point when Indian power in Patagonia and the Pampas was definitively broken.

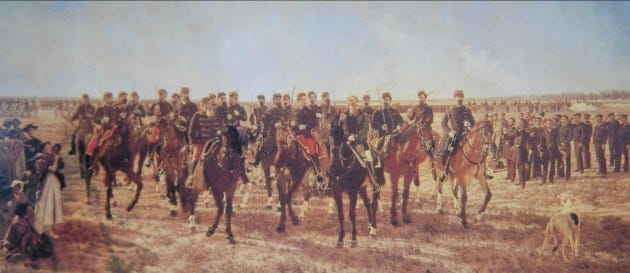

To white Argentina, the capture of Choele-Choel marked the triumph of civilisation over barbarism and savagery and the acquisition of full control over Argentina’s ‘internal frontiers.’ The arrival of Roca’s troops, timed to mark the date of Argentina’s independence on May 25, was famously celebrated - and mythologised - in the portrait by the Uruguayan painter Juan Manuel Blanes, showing Roca’s heroic army in the bandit citadel.

The monument commemorating that moment was built many years later, in the spot where Roca’s armies once gathered, and it contains much of the symbolism of Blanes’s picture. The front face contains an image of civilisation looking over the Patagonian ‘desert’. On one side a bas-relief of Indians with bowed heads symbolises the vanquished population, while a relief of men with European features with cloth caps and a plough on the opposite side signifies the European immigrants who settled the pampas and Patagonia in the wake of Roca’s ‘conquest’.

Aesthetically speaking, this is pretty crude stuff, but aesthetics aren’t the point here. The monument isn’t art. It is official, state-sanctioned propaganda, designed to preserve and disseminate a very specific understanding of Argentine history for posterity. There are many statues and monuments like it, in a country where every public place contains statues and monuments to the generals, politicians and statesmen who built Argentina in the nineteenth century, and almost every town bears the same street names.

As in so many other countries, Argentina has in recent years become a country where these monuments have been challenged; in direct action; in campaigns to remove statues of particularly despised or questionable historical figures, or change the names of streets and public places. Such efforts have often been focused on Julio Argentino Roca.

In 2017 the Roca monument in Choele-Choel was splattered with the red paint that still remains, in addition to the slogans accusing him of genocide and fascism. In the touristic city of San Carlos de Bariloche, the equestrian statue of Roca cuts a forlorn figure in the main square, where Mapuche activists and their supporters have covered it with red paint and similar slogans for more than twenty years.

Where these monuments were once erected to transmit a triumphalist version of the Argentine state and Argentine military power, they have now become public message boards, where these representations are being challenged in full public view. To whoever defaced these monuments, Roca was not the great statesman and civilising general, but a genocidaire who presided over the massacres of indigenous peoples, the forced marches of non-combatants, the destruction of indigenous families, the kidnapping of children, and the enslavement of their parents.

These defacements may have been carried out by the Mapuche descendants of victims of Roca’s campaigns, or by activists sympathetic to them, and they have taken place at a time when Mapuche and other indigenous peoples in Argentina and in Chile have been campaigning for inclusion, for territorial rights, for the recognition of injustices carried out in the past, and their continuation into the present.

Statue Wars

I’ve looked at these processes as someone who tends to be agnostic on the subject of de-monumentalisation. Or more precisely, I have mixed feelings about it. On the one hand I can’t bear the shallow indignation that the right exudes whenever its icons are challenged, mocked or defaced. It isn’t just the intellectual dishonesty or moral tone-deafness of white Southerners who reply ‘it’s only heritage’, when Afro-Americans call for statues of Robert E. Lee or Nathan Bedford Forest to be removed from public places.

Then there are the equally shallow and often hysterical accusations that the ‘Marxist’ or ‘woke’ left is ‘erasing our history.’ This supposed ‘erasure’ not only ignores the question of who is included or excluded by that first person plural; it also conflates the process by which certain historical events and individuals are commemorated and memorialised with the actual stuff of history.

Whether this conflation is deliberate or simply stems from ignorance is a moot point, but those who make such arguments tend to reduce ‘our’ national and/or imperial history to the level of a potted Ladybird book, in which history was made entirely by great men and the occasional woman, whose status and achievements can never be challenged or revisited, let alone ‘cancelled.’

A slightly more sophisticated version on this theme accuses the woke Marxist hordes of historical illiteracy, in attempting to impose a ‘virtue-signalling’ version of history on the past, which fails to understand that the people it attacks were ‘products of their times’. This tired ‘products’ argument has been around for a long time. Of course its true - up to a point. Moral judgements about historical figures made from the standpoint of the present don’t necessarily tell us much about the past unless we look at the historical context in which such figures were operating.

However that doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to make such judgements; try suggesting that Hitler and the Nazis, say, were a product of their times and see how far that gets you. Also ‘context’ is the last thing on the minds of our new anti-woke culture warriors. When a team of historians attempted to show the links between National Trust country houses and the slave trade, for example, they had Tory politicians practically foaming at the mouth.

History is rarely the issue for these people, even though they pretend that it is. So all this is not a little repellent. At the same time, I have reservations about the current vogue for toppling and defacing statues and monuments, which is unfolding in so many countries. It’s not the legality that bothers me. A bit of spray paint never hurt anyone. I wasn’t appalled - how dare they! - when the slaver Edward Colston’s statue was pushed off a a pier.

At the same time I didn’t celebrate it. I didn’t feel that it was a ‘victory.’ It’s not that I don’t recognise the political significance of statues. There’s a reason why French revolutionaries toppled or destroyed statues of kings. Or why the statues of Stalin, Lenin and Felix Dzerzhinsky were toppled after the fall of communism. These statues symbolised an oppressive and tyrannical political order whose time had come, and whose power was broken. The same could be said about the toppling of Saddam’s statue in 2003, as stage-managed as it was.

Statues have power. Or at least they represent systems of power and transmit messages of power. But in all these cases, symbolic acts of demonumentalisation marked the end of the physical, material power that such monuments represented. The same cannot be said about Colston’s statue, or the ‘Rhodes must fall’ campaign at Oxford. These are entirely symbolic victories, at a time when the left, for the most part, has been incapable of winning any other kind.

So I may not object to them, but I certainly don’t feel particularly moved by them either. I don’t see them as victories. My heart doesn’t quicken if ‘Empire Street’ is changed to another name. I won’t much care if the statue of the racist murderer Cecil Rhodes is taken down or not, because the presence or absence of his statue won’t change the crimes that he committed.

I’m also wary that the current vogue for demonumentalism can become an endless crowd-pleasing process, not only because many ‘great men’ from the past will always fall short of 21st century moral and political standards, but because the accusations laid against them can easily ignore the reasons for their place in the national pantheon that have nothing to do with what they are accused of.

Winston Churchill certainly had racist views, for example, but that isn’t the reason why so many people remember him. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson are not revered by so many American because they owned slaves, but for reasons that have nothing to do with that.

It’s certainly worth pointing out the moral contradictions in these protagonists of freedom. But by attacking every well-known individual who ever did or thought or represented anything wrong in the past, the left risks scoring purely symbolic points, while ignoring or demeaning those who sincerely regard such figures as part of their history and identity.

These are people who also belong to the flawed democracies that we are all obliged to live in together, even if we cannot stand each other most of the time. And leaving aside the deliberate malicious misrepresentation by rightwing culture warriors of demonumentalist campaigns, it doesn’t necessarily advance the cause of democracy or racial justice - or our understanding of history - if statues and street names are to become a permanent tug-of-war in an angry dialogue of the deaf over who should stand in the public square and who-should-be-called-what.

There has to be compromise and live-and-let-live. Not every statue can be pulled down. And not every street can be renamed. At the same time, the right cannot be allowed to present its national toy story as the only version of history on offer, and it cannot remain blind or deaf to the less salubrious and actually quite horrific attitudes and actions that national monumentalism so often ignores.

In a country that has more than its fair share of political horrors, and which seems to be engaged in a constant struggle between remembering and forgetting them, demonumentalism n Argentina is often accompanied by alternative forms of monumentalism, from plaques and murals commemorating the disappeared to the ‘30,000’ campaign in which headscarves honouring the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo are painted on pavements across the country.

It’s moving and inspiring to see the determination and creativity with which Argentinians are seeking to ensure that the crimes committed by the Argentine state are finally remembered or not forgotten. And as in other countries, these campaigns have received the same contempt, the same tone-deafness, and the same arguments from the right as we have come to expect elsewhere - with the difference that some of those who make them were participants in or supporters of the military dictatorship that once presented itself as the ‘civilising’ descendants of Julio Argentino Roca’s campaigns.

These ‘statue wars’ are part of an ongoing attempt by Argentina’s indigenous peoples to gain recognition in the present, and the focus on the ‘Conquest of the Desert’ represents a challenge to the once-untouchable myth of ‘white Argentina.’ Whatever happens to Roca’s statues, their defacement is part of an ongoing process of historical revisionism, reflected in a constant stream of books, articles, arguments and counter-arguments.

It will be interesting to see how all this plays out in the future. Because if the accusation of racist treatment of indigenous peoples were applied to all of the nineteenth century founders of the Argentinian state, there would hardly be a statue left standing or undefaced. I discussed these processes in Buenos Aires last month with the writer and activist Marcelo Valko. Marcelo is a former friend and comrade of the late great Osvaldo Bayer, and he proudly bears on his walls the signs of three streets in different Argentinian towns that were changed as a result of campaigns in which he and Bayer were involved.

Marcelo was keen to point out that these name-changes were democratically-achieved, through debates in local communities, and perhaps this is the key to demonumentalist campaigns across the world. In the end, demonumentalism should be a local process, in which individual communities decide for themselves what monuments they want to keep and what they want their streets to be called, and which new monuments they want to erect.

David Olusoga’s television series on Black Britain and the legacies of slavery contained a number of moments like this, in which schools or local people gathered to erect plaques commemorating some of the events and individuals that he described. Such moments of mutual acknowledgement and recognition do not ‘erase’ history, nor can they change it. They aren’t ‘victories’ of one side over another, but they can be victories for society as a whole, if they change the way we remember the past, find space to acknowledge the victims as well as the victors, and ask societies to take honest stock of where they came from, in order to ask the question of where they might be going.

We are still a long way from that, but in Argentina, as in so many other countries, it seems to me that these are the outcomes we should be aspiring towards.