Old Post: What Kind of Country?

Whenever politicians seek high office in this country, the subject of immigration will inevitably come up sooner or later, as the parties vie with each other to show how ‘tough’ they intend to be. The current Tory leadership election is no exception. Both contenders have gone to great lengths to demonstrate that they will be even tougher - tougher meaning crueller - in an attempt to regain ‘control’ over the UK borders.

The fact that these contenders have very little to offer the country, and very little to show for the great Brexit project on which the Tory party has bet so much, may explain the naked appeal to the xenophobic hard right that we saw last week. And they aren’t the only ones. At the fringes, the likes of Nigel Farage and Richard Tice can be found, once issuing dark warnings about migrant crossings in the Channel.

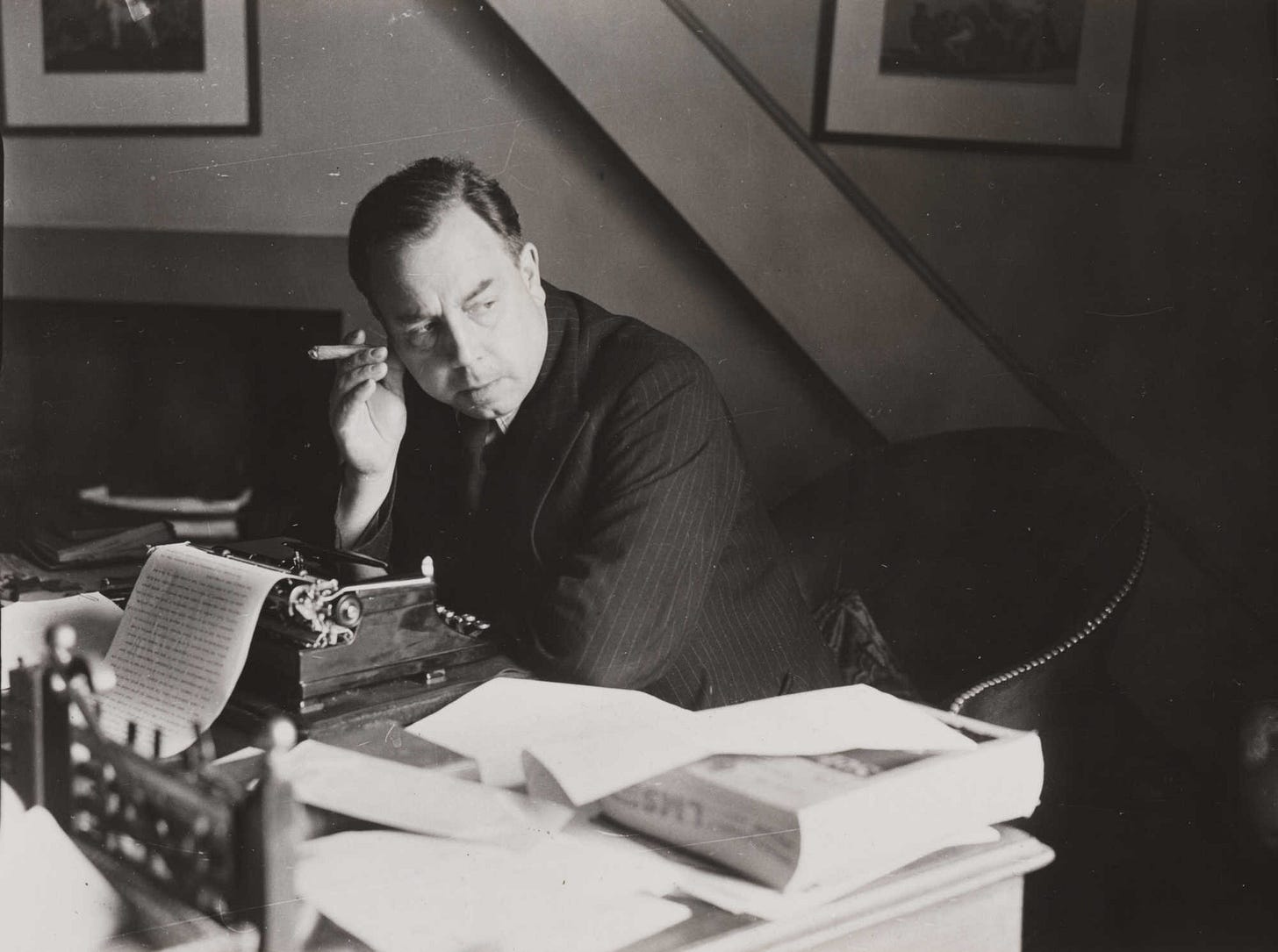

Very few things in history are entirely new. I’ve been discussing the writings of JB Priestley and George Orwell on the podcast that I co-host with Adrian Scott. And watching the petty leadership race unfold, I thought would be a good time to re-publish a post I wrote in April 2017, because much of what it says, and what Priestley once said, still applies, and the question I posed in the title has yet to be answered.

Every society, no matter how sophisticated or ‘modern’ it thinks it has become, contains within itself the ability to go forward and backwards. All societies contain the potential for tolerance and intolerance; for generosity, openness, and empathy and also for mean-spirited callousness, arrogance, selfishness and cruelty.

Every society includes people and communities that are open to the outside world and those that are fearful, resentful and bitter about their proximity to people who look and sound different to themselves, and who regard the presence of immigrants and foreigners as usurpers and intruders in ‘their’ country. There is no doubt which forces are now dominant in British society – and English society in particular. This has been obvious for some time, long before last year’s referendum.

It was evident not only in the sour national ‘debate’ about immigration and the ‘concerns’ which so many politicians have fallen over themselves to acknowledge. What were these concerns? That the UK was ‘full’ and was being ‘flooded’. That immigrants were taking ‘our’ jobs and also taking ‘our’ benefits, which meant that if they came here to work they were thieves and if they didn’t then they were parasites.

For years we told ourselves that immigrants were stealing ‘our’ houses, even when most of them were paying rent to private landlords. We imagined that devious foreigners all over the world were coolly scanning a list of the countries with the best health service before coming here to have their babies and steal ‘our’ beds, because they wanted to take advantage of our generosity.

We knew this must be true because that is what we believed certain categories of foreigners are like. We understood that the reason we couldn’t get an appointment with our GP was not because there weren’t enough GPs, but because there were too many immigrants. We knew – we just knew it – that the foreigners who came here contributed nothing, nothing at all to ‘our’ society. Our newspapers told us day after day that they were only here to take from us.

We heard that ‘mass immigration’ was an ‘invasion’ secretly unleashed by the Labour Party and the European Union in order to ‘rub our noses in diversity’. Even when we heard that ‘our’ national health service was crucially dependent on foreigners, we still wanted them to go home, because we wanted English nurses and doctors to treat us when we were sick or even when we were dying, even though there weren’t enough of ‘our’ nurses and doctors available.

All that was bad enough, but we also heard that immigrants were coming here who didn’t share ‘our’ values. Like the aliens in Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, they wanted to steal our identities and turn us into hollowed-out and watered-down husks of our ancient selves. We wondered what had happened to Christmas lights and Easter eggs, to ring-around-the-roses, hopscotch and Hovis bread, to village fetes and classic cars, and what on earth had we been thinking of when we allowed Muslim grooming gangs to turn our cities into no go zones which no cops ever dared enter and every councillor was engaged in a cover-up.

We saw women in burkhas and niqabs and we felt contempt for them because we knew that they wanted to impose ‘Sharia law’ upon us. At the same time we wanted to save these women, because, like UKIP’s Paul Nuttall, we feared that they weren’t ‘economically active’ and we believed in tolerance and equality.

We heard Poles speaking their language in public in ‘our’ streets and on the underground, and like Nigel Farage we resented this, because it was obvious that foreigners who spoke to each other in their own language were deliberately refusing to integrate with us, and because the sound of their foreign accents or the sight of a Polish delicatessen made us feel like strangers in our own land.

So we elected governments that told foreigners they must speak English, even as they were cutting ESOL provision that might have helped them to do this. We liked that authoritarian and dictatorial tone because it was our voice, not the voice of the metropolitan, latte-drinking elites who had inflicted this disaster upon us and transformed our country in some PC-speaking multicultural nation-of-people-from-nowhere.

We heard that our classrooms were overcrowded, not because our education system was underfunded, or because teachers were dropping out of the profession in droves, but because there were too many immigrant children in our schools who were holding our children back and forcing our sons and daughters to learn their languages and sing their songs and bake silly foreign cakes.

Even when there were no immigrants living anywhere near us we didn’t want them any closer because we knew what they were like. We knew that most refugees were not ‘genuine’ refugees, but ‘economic migrants’ who were so desperate to get ‘our’ benefits that were willing to get into leaky boats and die in the process, because we knew that foreigners who come from poor countries think like this.

Even when there was no doubt whatsoever that these refugees were ‘genuine’ – and that some of them were in fact children – we didn’t want to help them, because we suspected that they were too old to be ‘genuine’ children, and it didn’t seem right to us that we should have to help poor people from around the world when we needed to look after our ‘own people.’

Of course we weren’t really looking after ‘our own people’ either. When the numbers of homeless people rose, we put spikes in doorways or fined them for begging. When we heard that ‘our own people’ were being made to work even though they were sick and dying, we voted back in the government that made this happen. We had no problem with the bedroom tax, with ‘socially cleansing’ poor people out of London because we knew that poor people were not really ‘our own people’ who shouldn’t live in a city that was meant for rich people.

We supported punitive benefit sanctions, because we always assumed that we would never find ourselves living on benefits, and because we suspected that poor people – even ‘our’ poor people were not that different from immigrants in that respect. So let’s not pretend that we really cared anymore about the people from ‘somewhere’, as David Goodhart put it, than we do about the people who come from ‘anywhere’.

But let no one say that we are ‘racist’.

When Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU we feared and resented them, not because of their skin colour, but because we knew that both countries were largely filled with thieves, poor people and criminals who were about to flood ‘our’ country. We knew that, because ideas like this have been coursing freely and largely uncontested through English society for so many years now that they have begun to seem like common sense.

This isn’t entirely new. In JB Priestley’s English Journey, he talks of the German Jewish merchants who settled in his native Bradford before World War I. Returning to Bradford in 1933, Priestley noted

There is hardly a trace now in the city of that German-Jewish invasion’ and that many of these merchants had left the city or gone out of business: I like the city better as it was before, and most of my fellow-Bradfordians agree with me. It seems smaller and duller now. I am not suggesting that these German-Jews are better men than we are. The point is that they were different, and brought more to the city than bank drafts and lists of customers. They acted as a leaven, just as a colony of typical West Riding folk would act as a leaven in Munich or Moscow. These exchanges are good for everybody.

Priestley also noted a transformation that had taken place since the war that made these exchanges unlikely:

Just lately, when we offered hospitality to some distinguished German-Jews who had been exiled by the Nazis, the leader-writers in the cheap Press began yelping again about Keeping the Foreigner Out. Apart from the miserable meanness of the attitude itself – for the great England, the England admired throughout the world, is the England that keeps open house, the refuge of Mazzini, Marx, Lenin – history shows us that the countries that have opened their doors have gained, just as the countries that have driven out large numbers of their citizens, for racial, religious, or political reasons, have always paid dearly for their intolerance. Today, the same ‘cheap Press’ disseminates the same message and the same ‘miserable meanness.’

There were certainly caveats and contradictions in Priestley’s ‘great England’. He himself was savagely racist about the Irish, for example, but he nevertheless had a generous vision of what he wanted the country to be that could not be further removed from the one we now have:

It is one of the innumerable disadvantages of this present age of idiotic nationalism, political and economic, this age of passports and visas and quotas, when every country is as difficult to enter or leave as was the Czar’s Russia or the Sultan’s Turkey before the war, that it is no longer possible for this leavening process to continue. Bradford is really more provincial now than it was twenty years ago. But so, I suspect, is the whole world. It must be when there is less and less tolerance in it, less free speech, less liberalism. Behind all the new movements of this age, nationalistic, fascistic, communistic, has been more than a suspicion of the mental attitude of a gang of small town louts ready to throw a brick at the nearest stranger.

Ten months after the referendum, that ‘mental attitude’ is the dominant attitude in English politics in regard to the European Union and to immigrants and immigration, and a new and equally rancid expression of ‘idiotic nationalism’ is driving our steep moral descent into a country defined by the ‘cheap Press’ and the equally cheap politicians who have failed to oppose it.

This possibility should be at the centre of the debate about Brexit, and should not be marginalised by a conversation about the customs union or the single market. As Priestley warned, societies that behave like this will pay a high price for it, in ways that cannot always be measured in straightforward economic terms.

That is one reason, amongst many others, why the millions of people who don’t want to see the UK become a xenophobic backwater should make their voices heard as the Tory power-grab unfolds over the next six weeks, and elect politicians who can stand up for a different first person plural that includes migrants and foreigners instead of excluding them and blaming them for things they don’t do and for problems that they did not cause.