As promised, here’s the second extract from my writing memoir…down but not quite out in 80s New York…

It’s nearly forty years since I walked home to 546 East 11th Street with my keys ready to open the front door in an instant or jab a potential attacker in the eyes. These precautions were not based on urban paranoia. Fear was an entirely justified and common-sense response to a city that seethed with multiple threats. In the three years and half years I lived in New York I was mugged three times. Once I was punched in the face in Tomkins Square Park by two attackers, one of whom put a knife to my throat. On another occasion I was held up at gunpoint.

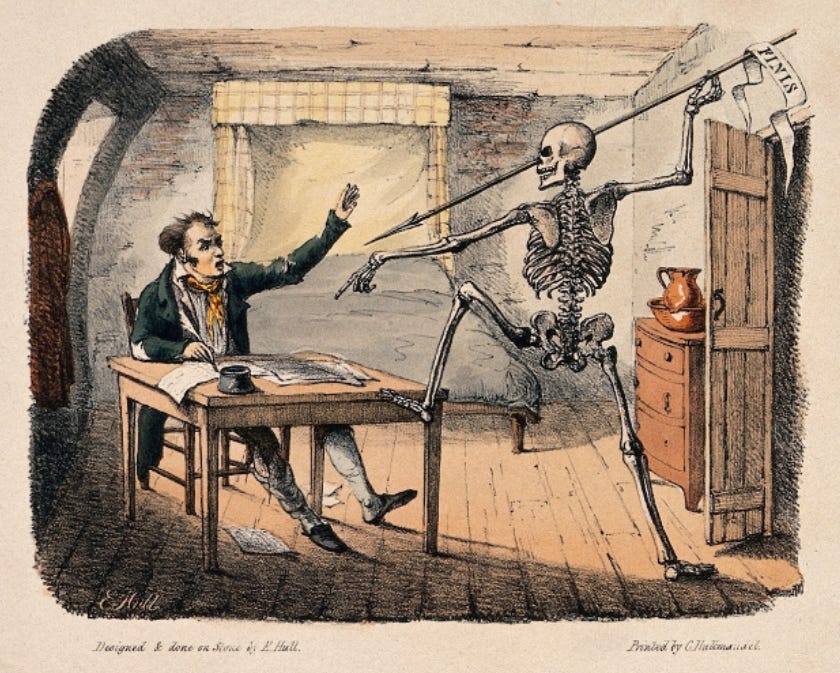

One morning I woke up in my ‘homestead’ to find a junkie creeping past my bed carrying my stereo. When I leapt out of bed and shouted at him, he dropped it and ran away. Two days later I woke up at the same time and was amazed to find the same man carrying the same stereo. Once again, I shouted at him, and he dropped it a second time. One afternoon I looked out of my window to find another addict trying to hang himself in the yard beneath my flat – an effort that only came to a halt when the acidhead on the top floor yelled “You can’t hang yourself, I’m tripping!”

Why did I put up with this? The most obvious answer is that I couldn’t afford to live anywhere else, but that would not be the whole truth. In the recent Netflix documentary on her life and work, The Center Cannot Hold, Joan Didion is asked about an episode from her 1967 essay Slouching Towards Bethlehem, in which she describes a five-year-old girl who had been given LSD by her hippie parents.

Asked by her nephew Griffin Dunne how she felt about this encounter at the time, Didion hesitates before replying “Let me tell you, it was gold. You live for moments like that if you’re doing a piece. Good or bad.”

Most writers will recognise the essential truth of this observation. Sometimes you come across people and events that demand to be written about, or which lend themselves perfectly to the story you want to tell. These subjects may not be edifying, but you don’t ignore them. I had originally arrived in New York in 1980 intending to continue to Latin America, where I hoped to write a book about my travels, but I was instantly gripped by a city that seemed to be tottering on the brink of collapse.

New York had only recently emerged from its near bankruptcies of the 1970s, and it felt to me like a Victorian city with its extremes of wealth and poverty, a place where it was possible to fall all the way to the bottom without any safety net to catch you. To the young would-be writer that I was, all this was both alarming and instantly compelling. ‘Here, all the sickness that is latent in so-called “cultured” societies like England screams at you in headlines and neon signs. You get a great view of the apocalypse from the World Trade Centre,’ I wrote to my youngest brother.

On the one hand, it was a city that felt familiar to me from Dos Passos, Henry Miller, Taxi Driver, and Escape from New York. At the same time, New York was a larger-than-life world-metropolis that recalled other literary cities. It was Brecht’s Mahagonny and Alfred Doblin’s Berlin. It was the Saint Petersburg of Dostoevsky, and the Paris of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil, in which ‘the charming evening, the criminal's friend/Comes conspirator-like on soft wolf tread/ Like a large alcove the sky slowly closes/And man approaches his bestial metamorphosis.’

I often thought of the medieval Paris of Rilke’s The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge as I walked through late twentieth century streets where it seemed equally possible to imagine that ‘Here and there a man, whose eyes had during the day encountered the relishing glance of his murderer, would be overtaken by a strange presentiment. He would withdraw and shut himself up, write out his last will, and finally order the litter of osier twigs, the cowl of the Celestines, and the strewing of ashes.’

From a writer’s point of view, the city was an endless resource, and I was conscious that I was witnessing a special moment in American history. In November 1980 Ronald Reagan won the US presidential election with the help of Jerry Falwell’s ‘Moral Majority’ Christian coalition. Even before Reagan’s inauguration the following January, taxis began to appear bearing images of Uncle Sam in overalls carrying an axe encouraging the population to GET IT DONE AMERICA.

In 1980 I read an article in the New York Times about groups of armed Nicaraguans carrying out military manoeuvres in the Everglades as part of a CIA covert operation to overthrow the revolutionary Sandinista government. I was astonished that the US government could brazenly plot the downfall of another government that it didn’t like in broad daylight. Even the liberal Times barely batted an eye.

It soon became clear what these preparations were intended to achieve, as the Contra war in Nicaragua got underway and the US government poured money and military aid into the dictatorships of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. The Reagan administration’s new ‘trickledown’ economic policies also had an impact on New York itself, as cuts to mental health and welfare programs increased the numbers of homeless people on the streets, many of whom were in a state of acute distress.

Even after Thatcherite England, this felt like something qualitatively new and distinctly worse. In the kitchen of my half-finished flat in East 11th Street I wrote short stories about New York lowlife, and filled notebooks with unfleshed-out character sketches and situations for a novel about the New York lower depths that I intended to call Summer in the City, but would have called A Season In Hell, if Rimbaud hadn’t already taken it.

Many of its characters were thinly fictionalised versions of the people I encountered every day, and much of the time there was no need to invent anything, because what was happening around me was so constantly bizarre. I never did write that novel. It was impossible to fictionalise a city that constantly outstripped anything my imagination could conceive, and non-fiction seemed incapable of capturing its outlandish extremes and fervid intensity. Instead, I concentrated on a new kind of writing that I had never done before, as I found myself singing and writing songs in a rock n’ roll band.

Ever since I first heard Bob Dylan’s reedy voice and jangling guitar on my parents’ stereo in the West Indies, music has been a constant presence in my life, and I have always been attentive to song lyrics. In my early teenage years, I was as influenced by singer-songwriters like Al Stewart, James Taylor, Buffy St Marie, Neil Young, Roy Harper and Harvey Andrews as I was by writers and poets.

Even before leaving boarding school, I had begun to teach myself to play guitar during the holidays. I worked my way through Chet Atkins and Mel Bay instruction manuals, and slowly progressed from ‘Skip to My Lou’ and ‘On Top of Old Smoky’ to Delta Blues and slide guitar.

By the time I arrived in New York my musical tastes had gravitated from psychedelia to pre-punk and New York New Wave, and I spent my first weeks in the city going out to see bands. It was partly because of my musical orientation toward the New York sound that I moved into a flophouse in the Bowery called the Palace Hotel above CBGB (Country, Bluegrass and Blues). This was the famous club, where Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie and so many New Wave bands had first made their mark.

I paid about two dollars a night for a wooden cubicle that stank of cabbage and urine, with a wire mesh above it and walls stained with the blood of crushed mosquitoes. The Palace was one of many similar establishments in the Bowery, most of whose ‘guests’ consisted of alcoholics, junkies, and the mentally-ill.

On my first night in the hotel one old man kept calling out “Jimmy, I’m dyin’,” to which his friend from another cubicle replied unsympathetically but no doubt accurately, “You ain’t fuckin’ dyin’ man, you ill that’s all.”

The toilets had no doors, to prevent addicts from shooting up. In the mornings I would find some of the clientele picking lice out of each other’s hair. The older men spent most of the day watching boxing on TV, and there was a kind of pathos in the fury with which these casualties of the American Dream urged the fighters to beat each other to a pulp.

At night the same men could be found out in the street, warming their hands round trashcan fires, drinking Night Train Express or Thunderbird wine, or coughing, moaning, and cursing each other in their cubicles while the noise from CBGB made the floor shake beneath us.

At that time, I had no idea then that I would end up playing at CBGB myself. One night I met a guitarist named Joe Braun in a Washington Square bar. Joe worked in a stationary shop and was carrying a pile of records, and we began talking music. Out of that conversation, we arranged a jam session in a midtown studio with two friends of his: a bass player named Kevin Delaney and a drummer named Mike Deitch, both of whom had played with Joe in various bands.

I had never played electric guitar before and didn’t know how to jam. Instead, I played three chords of what I thought might be the outline of a song. From the moment the rest of the band locked into the tune, I felt as if I had been instilled with some mighty power that I had never known existed.

We played those three chords over and over that night, and by the time the session was over we had agreed to form a band. None of the others could write songs or wanted to sing, and to my surprise I found I could do both. As a result, I found myself singing, writing songs, and playing rhythm guitar with three extremely talented musicians who had the patience to put up with my primitive technique and untutored vocals.

By the time I moved into my East Village homestead, we were rehearsing weekly, and I had bought myself a Fender guitar and amplifier. On cold winter nights I walked up and down my flat in a down jacket and hiking boots, working out tunes and writing song lyrics. Within a year we were playing our first gigs in local venues.

For a while we gave ourselves the very East Village name of Soviet Threat after the expression coined by Reagan’s Secretary of State Alexander Haig, before changing to the more enigmatic 1000 Violins. Our sound was hard-edged, with nods to psychedelia, Television, Joy Division and the Velvet Underground, but we were very different from many of the bands that came and went in the East Village in those years.

I remember one night I dropped in at the A7 after-hours club on the corner of Tomkins Square Park. I made my way past the usual crowd of young men and boys with crewcuts and Mohicans, studded leather jackets and army boots with bandanas around the ankles; and the girls with fluorescent pink and green hair, wearing leopard-skin trousers and short skirts.

Inside, the low-ceilinged bar was thick with smoke and a Chinese American punkette with vampirella hair was performing a striptease while two New Wave girls flicked cigarette butts at her. The punkette began to cry, and she had just gone to seek help from the doorman when a guy with green hair and a Mohican jumped onto the little stage brandishing a crucifix and announced a band called The Sick Fucks.

The other musicians slouched on stage behind him and a moment later the little club became a sea of pogoing heads and sweaty bodies bouncing off the walls while the singer screamed “Die! Die! Die!” over a deafening cacophony of tuneless guitars, bass and drums. This was immediately followed by another song dedicated to ‘our asshole president’, in which the singer dropped to his knees and wailed “Ronnay! I hate you Ronnay!” over a wall of noise played at the same breakneck speed. It was not music but a sonic attack, and even in my mid-twenties, I already felt too old for it.

This was not the world we belonged to, even though we were sometimes obliged to enter it. We liked songs with tunes, structure, and guitar solos, and the lyrics were as important as the music. I wrote about the Moral Majority, the wars in Central America, random violence, urban alienation and the collapse of civilisation, in songs like ‘Shooting Gallery’, ‘Elephants Graveyard’, ‘State of Siege’ and ‘Stations of the Cross’.

We may well have been the only band in history to reference Franz Kafka and Dostoevsky in a frenetic Cramps-style rockabilly song called ‘Telling Lies About Josef K.’ We quoted Orwell’s ominous phrase ‘We are the dead’ from 1984 in a Joy Division-influenced number, in which I howled desperately ‘the building’s on fire but I can’t get OUT.’

“Why can’t we just sing ‘you’re my woman now’?” asked one of various exasperated drummers who came and went, but we weren’t that kind of band. We believed rock and roll could change the world, and most of the lyrics I wrote were political in the broadest sense of the world and expressed levels of alienation that were very much par for the course for East Village bands in those years.

We played our first indoor gig in front of two people at the Pilgrim Theatre in East 3rd Street – a former music hall run by an amiable Rastafarian named Patrick which was just around the corner from our rehearsal studio – and just up the street from a row of houses where most of the heroin in the city was sold.

A few months later I saw a little-known band called REM play their first New York on that same stage to a packed auditorium, and later that night a local band called the Bloods who supported them was held up at shotgun point in their dressing room. Our main stomping ground was CBGB. The sound engineer liked us, and so did Television’s bassplayer. We played there regularly. On one famous night we played to a packed house that consisted almost entirely of the staff from the Strand Bookstore where I worked.

On another occasion we managed to convince the AFL-CIO union federation to let us play in a one-day concert in Central Park. For a few weeks we fantasised about hiring a helicopter like the Rolling Stones and imagined ourselves playing in front of a vast crowd. Luckily for us it was too expensive, because when we arrived in Central Park, we found only a handful of union members and their families eating picnic lunches, who listened to us with bemused incomprehension.

For the best part of three years, we did what Lower East Side bands were supposed to do. We rehearsed at least twice a week and refined our sound. We went out to clubs with our demo tapes to hustle for gigs. Whenever we played live at A7 or CBGB we stuck homemade posters on walls and lampposts to publicize ourselves. We got ourselves interviewed on a local radio station.

At one point I took singing lessons with the mother of one of our drummers, who tried in vain to teach me operatic scales. Music seemed to surround me wherever I went. In Spanish Harlem the former drummer of The Supremes lived in the flat above. I sat on the stoop and played endless salsa jams with a cocaine dealer named Hector, who owned the building next door.

Hector asked me to play with him, and these were not invitations to be turned down. The rumour in the street was that Hector had once served time for shooting one of his competitors in his back yard. He would bring his own keyboards onto the sidewalk, and he usually arrived looking wild-eyed, with traces of white powder on his nostrils. I would try to play along on my electric guitar and portable amp, while the old men played dominoes on the other side of the streets and few younger listeners came over and tried to dance to our clunky Latin-flavoured improvisations.

Had it not been for 1000 Violins I wouldn’t have stayed in New York for so long. But it was thrilling beyond anything I had imagined to sing my own songs in a band, and play with musicians with such feeling and technique. Though I wrote the words and chords, the arrangements were always collective and there was a real sense of communion between us, that found expression in the music and also in the hilarity and banter that accompanied our gigs and after-midnight rehearsals.

In the winter of 1983, we shared a bill with Patti Smith’s guitarist Lenny Kaye at CBGB. That night it snowed so heavily that cars were buried in snowdrifts and the subways were closed, so that we were unable to bring our equipment from Brooklyn to the Lower East Side.

Luckily, the CBGB management was sympathetic, and agreed that we could use their drums and PA system, and we walked all the way from Brooklyn, bursting into the club carrying guitars in our freezing hands, with snow on our scarves and long coats like arctic explorers. We played our set and stayed to watch the other bands. At dawn we walked back across the majestic Brooklyn Bridge that echoed with our laughter and the shouts of stranded but joyful commuters throwing snowballs at each other, and looking out across the river where Hart Crane once observed seagulls ‘Shedding white rings of tumult, building high/Over the chained bay waters.’

What a simultaneously exhilarating and hellish experience Matt.

I guess it was always comforting to know that you potentially had a ticket out when you needed one.

Did you record any of your songs?

Did the stereo work after being nicked and dropped twice?