Before I came to the Atacama, I hadn’t looked at stars for a long time. From time to time I saw a few stars through a haze of urban light pollution. But there were never enough of them to hold my attention. Out here in the desert, it’s a different matter.

One night last week, we lay on our backs on wooden palettes outside San Pedro de Atacam, looking up at a sky brimming with stars, while an Indigenous astronomer expertly guided us with a laser pen through the lunar calendar, the motion of the celestial Equator, the location of the Southern Cross, the Diamond Cross, Sagittarius and other constellations that I’d heard of but never actually seen. Afterwards, we looked up through telescopes at the moon, a time-lapse image of a nebula and a galaxy containing millions of stars.

Our guide also talked us through Indigenous ‘dark constellations’ – the great lama and its baby; the fox chasing the baby; the serpent and the toad. We saw the sheen of dust covering the Milky Way, which Indigenous Atacameños regard as a river containing the spirits of their ancestors. As my untrained eye followed our guide’s laser pen, I found myself wondering what else was up there.

I thought of Kurt Waldheim, the war criminal-turned UN General Secretary, whose voice is now circling deep space on the Voyager Golden Record, along with Chuck Berry, Glenn Gould, and the Bavarian State Orchestra. I thought of the Chilean writer Nona Fernández’s remarkable memoir-essay Voyager: Constellations of Memory, in which she links the constellations that she observed in the Atacama to the neurons in her mother's brain, to individual memory and to Chile’s collective memory of dictatorship and the disappeared.

Her book culminates in an account of the Carl Sagan series Cosmos, which she watched as a teenager during the Pinochet years, as she imagines the two Voyagers that Sagan helped prepare, ‘moving through space at this very moment, travelling with their golden records bearing our attempts to register the best of humanity.’

Today, there many objects moving through space that do not necessarily represent the best of humanity. In May 2025, the Union of Concerned Scientists Satellite Database listed about 9,800 active satellites in Earth’s orbit - a figure that rises to 27,000 according the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, if older satellites, rockets and space junk are taken into account. Governments, universities, private corporations such as SpaceX, Starlink, One Web and Amazon are all filling the skies with satellite constellations.

From my desert vantage point, I couldn’t see them, but I knew they were out there: comsats (commercial satellites): Starlink/Netflix combos; military satellites and space shuttles. Some of them were spying and gathering intelligence, or guiding bombs to their target in Gaza or Ukraine. Others would be streaming Better Call Saul or Sex Education, promoting Amazon Prime or GPT Chatbot, or enabling users to post selfies on Instagram.

In the coming decades there are likely to be more and more of them, as the militarisation and commercialisation of space intensifies. But here in the Atacama, there are also organisations that are looking at the stars for entirely different reasons.

Because of its high altitude, dry climate, generally cloudless skies, and lack of light pollution, the Atacama has become the location for some of the most advanced astronomical observatories in the world. Last week, I was lucky enough to visit the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) - the most powerful radio telescope in the world. Established in 2011 and fully-operational since 2013, the observatory is a multinational project involving the European Southern Observatory (ESO), America, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Chile.

The ESO’s stated mission is ‘to enable scientists to discover the secrets of the Universe for the benefit of all’ , and the ALMA is the jewel in the crown of the Atacama’s observatories. In an era in which space is dominated by military and commercial agendas, I was curious to see an international observatory dedicated entirely to the search for humanity’s cosmic origins.

From the main road leading through the Salar de Atacama, we could see the ALMA’s Operation and Support Facility nestled on the slopes of the Andean Cordillera, beneath the Licancabur and Lascar volcanoes. After screening at the entry gate, we drove up the dirt road past the ruins of old Indigenous shepherd hits, towards the offices and hangars - the only part of the observatory visitors are allowed to see.

We couldn’t see the huge radio telescopes on the Chajnantor Plateau, further up, at an altitude of 5,000 metres. There are 66 of these mighty telescopes, which are moved back and forth and clicked into fixed bases, across a distance of 16 kilometres:

These telescopes are moved by giant transportion vehicles with 1,000 horsepower engines, whose drivers - most of whom come from a mining background - need oxygen to work at such high altitudes. Their movements are scheduled months in advance, according to the requirements of scientists across the world, who make use of the facility. The ALMA is essentially a data-collecting centre, which gathers information for others. Every year, proposals are submitted to the observatory and then peer-reviewed, and accepted projects will then determine the movements of the antennae, which will be scheduled months in advance.

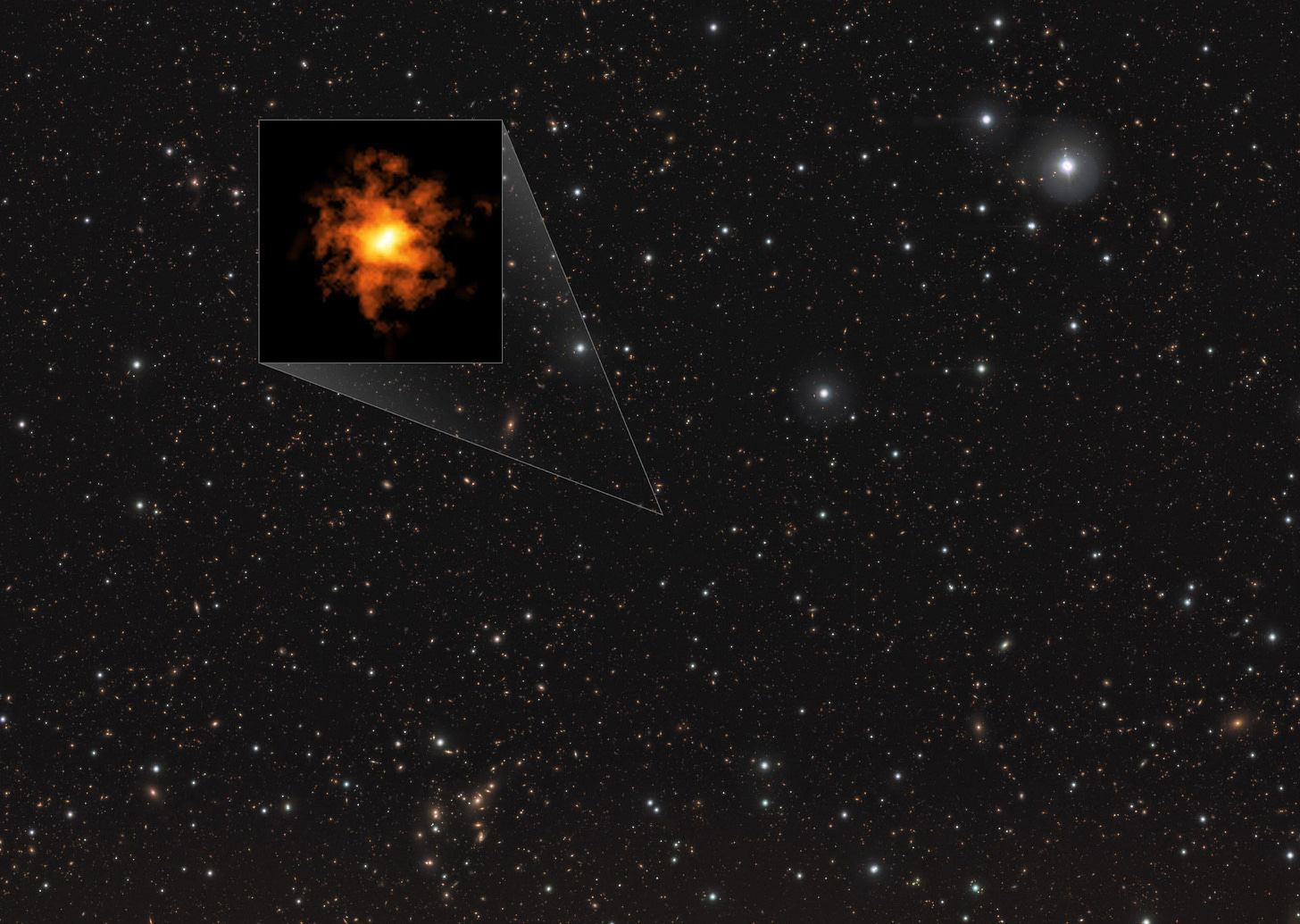

This mobility, coupled with the exception e results have often been sensational. It’s antennae have captured images of new-born stars from 500 years ago:

And ‘rotating galaxies’ that existed only 700,000 million years after the Big Bang:

The combination of bandwidth and mobility has enabled the ALMA to take unprecedented high-resolution images, zooming in on planets, stars, and galaxies in the ‘cold universe’ that are invisible to the naked eye. As a result, the ALMA has become both a cosmic narrator and ‘time machine’, piecing together and reshaping our understanding of the earliest stages of the Universe. These achievements have enormous scientific value, but to what extent does the ALMA contribute to ‘the benefit of all?’

I asked our guide Nicolas Lira, the ALMA’s Education and Public Outreach Coordinator. Lira has been working for ALMA for twelve years now. An eloquent and thoughtful former journalist, he has a background in physics and science and used to work in the tourist industry, television newsrooms. None of this suited him. ‘ I started to seek some purpose, where I could combine my skills, and I found a home here, combining science and science communication skills, and working for humanity and not for profit.’ I asked him how ALMA’s work benefited humanity.

We are trying to explain how life came to be in our universe, because everybody has these fundamental questions: about how we came to be on earth, about how we came to be alive, and what will happen to civilisations in the future. Of course the timescales are so big that it might not seem important for a single life, but I think what differentiates humans from other species is that we actually ask ourselves these questions, and we can actually project ourselves into the future and into the past.

But how would he explain the significance of these discoveries to the lay person?

If you want to improve life or how to understand life, you have to understand the origin of what can sustain life. And that cannot be done without astronomy. Or course, neither can it be done without biology or a fundamental science. But astronomy is one of the buildings blocks of that knowledge.

Given the shortness of a human life, was it really possible for ordinary people to comprehend the significance of astronomical discoveries that ranged back and forth across unimaginable timescales? Again, Lira had an answer:

Most people are able to understand that we are a small part of a very big universe. That’s what makes us look at the sky or at the ocean, and whenever you look at the moon you see the vastness you do feel that you are something small in something very big. And humanity has been trying to build a heritage over the centuries, over millennia. When we started writing on walls, 30,000 or 3,000 years ago, that was the beginning of building a heritage. So I think most people do have a sense of making a small contribution to a bigger heritage.

Though Lira pointed out that this sense of contributing to a heritage was not limited to astronomy, he nevertheless insisted that astronomers occupied a unique and privileged position that enabled them to ‘take a picture of the universe, so complete and so detailed that it will allow humanity to guess how it was before and how it was going to be afterwards.‘

These were fine words, and as Lira showed us round the laboratories and control rooms where data from the radio-telescopes was collected, 24 hours of every day, I was impressed by the technical expertise that had been directed to what was essential an altruistic exercise in pure science: It was a thrilling and awe-inspiring sight to see one of the antennae, some thirty foot high, next to its transportation carrier:

This was technology at the cutting edge, with no military or commercial implications. In a world increasingly governed by yahoos, it was a testament to the benign possibilities of international scientific cooperation. As we drove away, I thought of Johannes Kepler, the seventeenth century astronomer, and mathematician who discovered the laws of planetary motion.

Kepler’s personal and professional life was marked by tragedy, financial insecurity and constant setbacks and reversals. He lost three children before the age of six within a six-month period. His first wife died of fever in 1611. He lost three more children with his second wife Susannah, who also died young.

He was financially dependent on various patrons, and subject to the shifting winds of religious intolerance. He lived in an age of violence and fanaticism – against a background of imperial conflict and the barbarism of the Thirty Years War. His mother was put on trial for witchcraft - in part because of a reference to a herbalist in his ‘science fiction’ novel Somnium.

And yet Kepler never stopped looking at the stars, and studying the cosmos that be believed had been created by God. Our technology-saturated age is also an age of violence, religious fanaticism, moronic quasi-religious superstitions pumping endlessly through a supposedly interconnected world, that continues to generate polarisation, conflict and division.

Where Kepler’s peers once tried his mother for witchcraft, tens of thousands of people in the 21st century believe that viruses are carried by 5G, that the world is governed by cannibal celebrity-elites. We live in an age in which men run down pedestrians in the name of God, and target abortion clinics that they believe are the work of the devil. The day before I lay in the desert looking up at the stars, Israel obliterated a café in Gaza with a 500 lb bomb - guided by satellite.

The ALMA belongs to a different world, and to different possibilities, that are still present even in our new age of barbarism and our wilful embrace of malevolent stupidity. From the world’s driest desert, it is probing the spaces between the stars in an attempt to tell humanity where it came from and where it might be going. As I returned to San Pedro de Atacama, I felt privileged to have seen it. And I took some consolation from the endless reminders of our fractured and increasingly demented world, in the knowledge that Kepler’s heirs were using this mighty outpost of science in the Andes ‘for the benefit of all.’

They move elements of the Very Large Array around the Scorching Plains™ of New Mexico on railway tracks. Including across US-60.