In most deserts, the dead don’t last long. Most of us will know this, even if we have never been anywhere near a desert. Maybe we’ve read newspaper reports of the migrants who die of dehydration or exposure in the deserts of northern Mexico or southern frontiers - their bodies reduced to desiccated, leathery husks with only a cursory resemblance to a human. Or perhaps we’ve seen images of animals on the fringes of the Sahara, reduced by sand, wind, sun and predators to the bare white bone that often appear in news articles about desertification drought and climate change.

In the Atacama an entirely different process occurs. Here, extreme aridity and a nitrate-rich soil have combined to impede the bacterial growth that would normally finish off any organic matter buried or left out in the open. These conditions have turned the desert into a natural mortuary, where the dead can be preserved in a mummified but still-recognisable physical form for hundreds and even thousands of years.

The history of the Atacama is replete with such remains, from the mummified bodies of dead miners, and the victims of serial killers, to political prisoners murdered and dumped in the desert during the Pinochet dictatorship. But the oldest bodies in the Atacama belong to one of the most intriguing, mysterious and enigmatic of all South America’s Indigenous peoples – the marine hunter-gatherers known as the Chinchorro people. ‘Chinchorro’ is a modern term that history has bestowed on the peoples who first settled the Pacific coasts from Peru into northern Chile about 7,000 years ago.

Although the peoples who formed what anthropologists call the ‘Chinchorro complex’ have long since vanished from history, they have acquired a remarkable historical afterlife as a result of the cultural practice for which the Chinchorro are most famous – their highly-skilled and meticulously-executed techniques of artificial mummification.

About 5,000 years ago – some 2,000 years before the Egyptians, the Chinchorro began to mummify and decorate the bodies of their dead. They continued to do this for more than 3,000 years, developing an intricate methodology and belief system that continues to dazzle and intrigue anthropologists.

This scientific fascination wasn’t always present. When the German archaeologist Max Uhle first began excavating mummies from Chinchorro beach in 1917 – their significance was not fully-appreciated. This was a period in which archaeologists and anthropologists still tended to associate cultural and religious sophistication with urbanisation and priestly hierarchies, rather than ‘primitive’ or ‘savage’ societies where such sophistication was supposedly absent.

Having spent much of the last two years delving into the works of Victorian anthropologists who expounded such theories, I had already become wearyingly familiar with these tedious speculative trajectories before I came across the Chinchorro. Here we go again, I often found myself thinking, as I trudged through yet another Victorian gentleman’s account of the ‘descent of man’ through various stages of savagery and civilisation. ‘Savages’ - a word applied to virtually any Indigenous people, invariably occupied the lowest rung of humanity, with little to distinguish them from animals.

Such peoples, the consensus held, were a retarded form of humanity. Their lives were short, nasty and brutish. Devoid of culture, incapable of domesticity, love and affection, prone to cannibalism - they were doomed to ‘extinction’ by the march of (white) civilisation - an outcome that was tragic but also inevitable.

None of these scholars knew of the Chinchorro, because no one did. And it would have been interesting to see how they would have have reacted if they had known, because these hunter-gatherers could not be further removed from the reductionist stereotypes that still continue, in various insidious ways, to underpin western attitudes towards Indigenous peoples.

The Chinchorro were not urbanised, which might have at least put them in the ‘barbarian’ category that 19th century scholars conferred on the Incas and the Mayans. Living in small isolated groups on the beaches of the Pacific, they built no permanent settlements, and wore no clothes except for reed skirts and loin clothes. Their technology was primitive, but adequate for their material needs. For thousands of years, they lived from fish, shellfish and hunting sea lions and other animals. And yet they developed ingenious and artistic techniques of artificial mummification, using only the materials that were available to them.

The Chinchorro understood enough about the human anatomy to know what decayed and what survived. They removed the brain and internal organs, before peeling the skin to replace removed organs with reed and mud. They then created clay masks to cover the face and skull, which they painted using red, black and white clay or manganese. They used sticks to strengthen the arms and spine, reed ropes to hold these structures together or bind the skull to the spine, and topped these creations with human or animal hair.

Since Uhle’s discoveries in 1917, some 300 of these mummies have been found in various places in the Atacama, particularly in and around the city of Arica, most of which have been discovered in the last fifty years. On our first day in the city, we drove out to see some of them at the University of Tarapacá’s archaeological museum in the former oasis of the Azapa Valley. The mummies are housed in a grey block-like building, amongst tall, swaying palms and banana trees, alongside the foundation stones of an old Spanish hacienda.

I had seen photographs of these mummies before, but it was deeply moving to see some fifteen bodies behind a glass screen in a specially-heated room with dimmed lights. Lying on their individual benches, they seemed hover in the semi-darkness - inhabitants of some intermediate zone between the living and the dead.

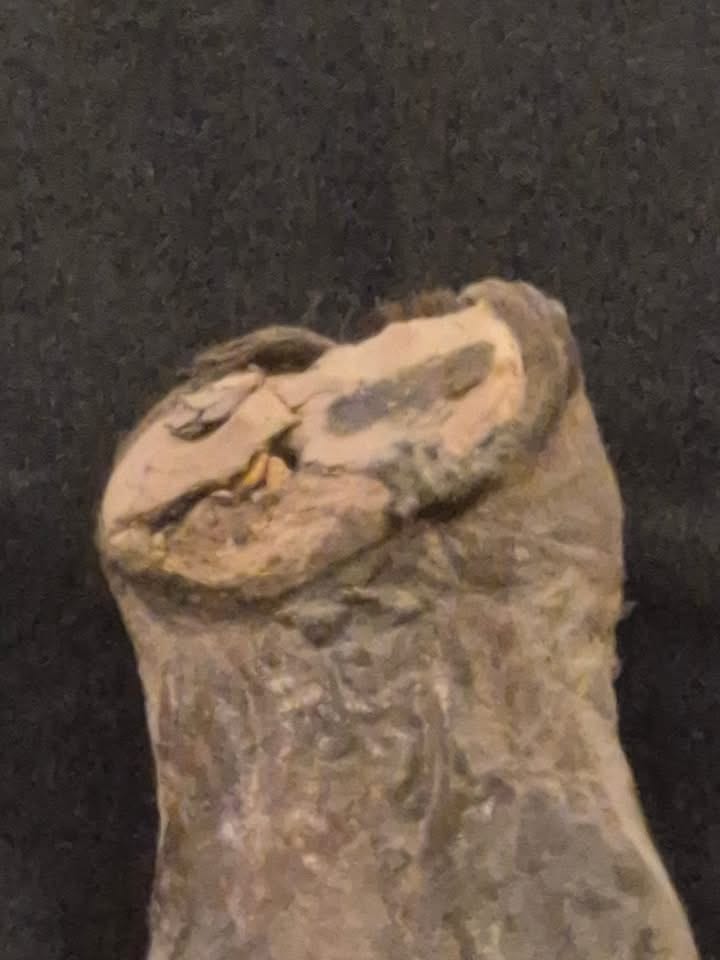

Some had masks on their faces, with the slits for eyes and mouth that were part of Chinchorro mummification practices, and which enhanced their humanity. Some had decayed to the point when they had no feet or hands; others had all their fingers remarkably intact:

What struck me about these mummies was the tenderness, as well as the artistry that went into their creation, and also their egalitarianism. Because unlike the Egyptians, there were no hierarchies involved. They Chinchorro didn’t just mummify kings, queens and aristocrats - they mummified everyone. Children were a persistent object of mummification. The youngest children – even foetuses - had been mummified.

One display case contained an embryo attached to a stick , with a flattened space on which an eyes and a mouth had been drawn in order to create the semblance of personhood:

The mummification of children, some scientists believe, reflected the high incidence of infant mortality amongst the Chinchorro people, that may have been a result of the high incidence of natural arsenic in Atacama rivers. Whatever the cause, it was clear that the Chinchorro valued their children enough to preserve them into the afterlife. And with the help of the desert, they succeeded.

After so many thousands of years, these mummies have inevitably experienced some decay. These striking creations by the local artist Paola Pimentel give an idea of who they might have looked at the time. Here:

And here:

Whether real or imagined, these bodies suggest an attitude to death that is very different from the Christian tradition. In medieval and early modern Europe, death was often depicted as a grim warning. Tapestries, paintings and mementos mori emphasised the decay of the body as a reminder of the ephemeral nature of human life - the better to encourage a virtuous and devout life and concentrate attention on the fate of the soul in the hereafter.

The Chinchorro refused to accept this inevitability. Living in a world where death was a constant and inexplicable presence, they set out to beautify and preserve even the smallest and most insignificant members of their community who were being taken from them. They buried their dead alongside their camps, with slits in their masks to create an avenue of communication between the dead and the living.

The museum isn’t just concerned with the dead. It also shows the tools the Chinchorro used to fish and hunt with, from harpoons and arrows to knives and hooks made from shells. It discusses the propensity to extososis (benign bone tumours) in the ears of adult Chinchorro males, probably as a result of diving; the damaged teeth amongst female corpses due to stripping flesh and chewing sinew to make it soft.

When we returned to the warm sunlight, there were groups of local schoolchildren were sitting under the palm trees listening to music and looking at their phones. They were 21st century teenagers, completely and fully alive, wholly immersed in the present and in each other. But they all shared a common destination that is part of the human predicament, whoever and wherever we are. And watching them, I thought of the brilliant Chilean writer Nona Fernández, and her compelling reflections on space, astronomy, the Chilean disappeared in Voyager, and the universal human desire to be remembered, and to leave something of ourselves behind.

In the West at least, we still tend to push death to the margins, and only recognise its significance only when we can no longer avoid it. One of the reasons why the pandemic came as such a collective psychological shock - in Europe and the United States at least - was because we live in societies where death is still something of a taboo subject, and where many of us have become so accustomed to continued longevity that we are not supposed to die.

Mesmerised by the false promises of ‘wellness’ and a certain idea of eternal youth perpetuated by the likes of the Kardashians, Paris Hilton or David Beckham, we have constructed our own imagined biological hierarchies, in which whole categories of people can be effectively written off for being old or having ‘underlying health conditions’, as both Boris Johnson and Trump and so many Internet pundits tried to do during the pandemic.

And yet it is still possible to see ourselves in the Chinchorro mummies. I discussed this fascination with the anthropologist Bernardo Arriaza. As a young undergraduate in the 1970s, Arriaza studied under the late paleo-pathologist Marvin Allison In the United States, where he first became aware of the Chinchorro. Arriaza was intrigued and moved by what he saw. In the 1980s he moved back to Chile, and settled in Arica in order to study the Chinchorro mummies. This decision was both scientific and personal. The science writer Heather Pringle has written of the ‘deep, unexpected sorrow’ that Arriaza once felt at his mentor Marvin Allison’s dissections of the Chinchorro.

Since the 1980s, Arriaza has written books and dozens of articles on the Chinchorro, and he has also been instrumental in disseminating a very particular humanistic interpretation of Chinchorro culture. I was keen to meet him, and we arranged a meeting at the University of Tarapacá offices in Arica. For someone who has spent much of life studying the dead, Arriaza was remarkably chipper, upbeat and cheerful:

He explained his ‘Quixotic’ commitment to the Chinchorro in the Americanised English that he picked up in his youthful studies in the US, and told me why he thought the Chinchorro began to mummify their dead:

The key element is that this fixation with death became the central thing for them. I think we need to imagine a possible scenario when you have a small group of people living in an environment which is very hard. It’s cold. There’s a lot of UV (ultra violet radiation). There’s not too many natural resources to use, and then you have high rates of mortality and you don’t know why. So that’s kind of a mystery, and then because of the grieving, the empathy, the desire to preserve this little person, these little children that die. So that emotional grieving, caring – that’s how it started. And then people came and they liked what they saw. They preferred to see an ornamental body, a beautiful decorated body rather than a decaying corpse.

Arriaza has called the Chinchorro mummies ‘superb go betweens with the spirit world’, but he also admits that scientists still don’t fully understand the belief systems that underpinned these practices:

I sometimes wonder what the Chinchorro would have thought, all these people dying all the time, they didn’t know why, all this mystery of life you know, how they rationalised it. You’re seeing today, with all this Covid virus, and people were having different reactions, from the more logical and more complex things to the more theological and more political points of view. So in the case of the Chinchorro, I wondered myself – I don’t have the answer – how they perceived this silent death of children and themselves.

In the 21st century, many people - usually rich people – dream of perpetuating themselves through transhumanism, cryogenics or other forms of technology. Did the fascination with the Chinchorro mummification also speak to that fear of annihilation?

I think in general that we as humans, we don’t want to die. We always want to preserve something of the people that we love or of ourselves. We want to preserve a picture, a moment, a bit of hair, an image, with cryogenics or something like that. We do a lot of surgery and we improve ourselves, which is very Western, this looking for eternal youth. So in a sense you seek this eternal youth through surgery, medicine and better health, but the bottom line is, you want to be there, you want to be a permanent something. And in the case of the Chinchorro, they also wanted to be there at the end, because we want to stay as much as we can. And we also want to remember those we loved.

In blending the past and the present through their ancestors, didn’t mummification also offer a consoling message to the living about the future: that you too will end up like this. You will also be preserved?

That’s very interesting. Because when people see the mummification process, you also know what is going to happen to you. Belonging to this group, knowing what the elders are saying, what you should do, how you should behave, and this is what’s going to happen to you in a good sense. You’re going to be mummified, you’re going to be part of the group, and you want that sometimes, you know? It’s like, we all die, we think of where are we going to be buried, what kind of ritual do you wanna have when you’re gone. Some people say ‘read this stuff, I want this in my epitaph’. So with the Chinchorro, I think we can envision a little bit what would have happened.

Surprisingly, this student of the ancient dead also believes that the artistry and creativity of the Chinchorro have a message for the 21st century on ‘the beauty of life, the enjoyment of life’, which can be extracted not only from the stress and trauma experienced by the Chinchorro, but also from the ‘mystery and wonder’ these inexplicable tragedies evoked in them:

That’s also the beautiful thing of when we study ancient culture, you know? You see this invisible thread that still unites the past and present, and we tend to think ‘oh the present is here, the past is over there’ and there’s no connection. But there is a connection in the way that we think, in the way that we prepare food, in the way that we treat the dead, in how we perceive order and conflict. I mean supposedly we have evolved so much and we still have all these horrible wars. So we say oh, these people were savage, and here we are the novel Homo sapiens that is thinking, and we still do so many nasty things.

We do indeed, and right now there are a lot of very nasty things going on, many of which involve entirely avoidable deaths. And in these circumstances, it can be instructive to contemplate that ‘invisible thread’ that connects the post-pandemic present to the distant past. And even in a technology-saturated world, that dreams of transporting consciousness onto a computer or an avatar, maybe the Chinchorro can remind us of this very simple, but often ignored fact: that we don’t live forever and some of us will go before our time, and that faced with this common predicament we might, as Arriaza suggests, dedicate more time to the beauty of life and learn to value even the most seemingly insignificant members of our societies.

And one of the most interesting things about the Chinchorro is how these ancient mummies have become part of the present-day identity of Arica itself, and an inspiring lesson in science communication with implications that reach beyond the Atacama. And that is the subject of my next post.

Hi Matt

Is this an abstract from your book?

Hi Cill. No it isn’t. But some of these letters might find their way into a book…I hope.