From Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to the Mad Max franchise, deserts are ubiquitous components of our worst imagined future - the barren lands where civilisation dies and feral bands engage in violent competition for scant resources, almost none of which come from the desert itself.

Deserts lend themselves easily to these fictional scenarios, because deserts have long been imagined by outsiders as dead lands that are unfit for humans. But the Atacama has other stories to tell, and I was keen to hear them.

Before coming here, I was intrigued by the atrapanieblas (fogcatchers) - a Chilean invention which uses Raschel mesh to ‘catch’ fog moisture and turn it into water. This mesh is commonly used in athletics and sports wear, and agricultural packaging. The Chilean variant uses vertical panels, stretched out like hides between two tall pillars, to trap the moisture from the fog known as the Camanchaca , which drifts in most days from the Pacific Ocean along some 1,200 kilometres of coastline.

I wanted to see how this technology worked in practice, but my attempt to do so turned out very differently to what I expected - a near-disaster, followed by an experience of the desert that I won’t easily forget.

The day began in Iquique, when I sent a request to the Universidad Católica del Norte, asking to visit the UC Atacama Desert Station at Alto Patache, where one of Chile’s ‘fog oases’ were located. I had applied before, without much luck, and nothing seemed to be happening this time, so I went off to the famous Zofri shopping mall, basically because I had never seen a shopping mall in a desert before.

Iquique is one of the largest duty-free ports in South America, and the docks were stacked with containers some seven stories high, alongside a garish Macworld mall containing all the commodities that you would expect to find anywhere - except that some of the mobile phones and computers would have been made with components extracted from the desert itself.

Shortly after that, I got a surprise call from Milton Aviles, the station manager at the Alto Patache station, to say that the station’s director in Santiago had given me permission to spend the night there.

I immediately accepted. Jane was ill with a cold, so I went alone. Around 8 o’clock, Milton and his mate Jorge picked me up. We drove south for about 45 miles along the notoriously accident-prone coastal road from Iquique to Antofagasta, before turning eastwards along the ‘salt route’ that connects the Salar Grande salt mine to the Puerto de Patillos.

To see these giant trucks laden with salt, moving down to the coast, while empty trucks headed up to the mine from the opposite direction to fill up, was to bear witness to Chile’s gargantuan extractive operations in the Atacama, and the 24/7 supply lines that connect the desert to the most far-flung ports with relentless precision. After about half an hour, we left the road and drove along a bone-crunching service road that followed the direction of an electricity pylon.

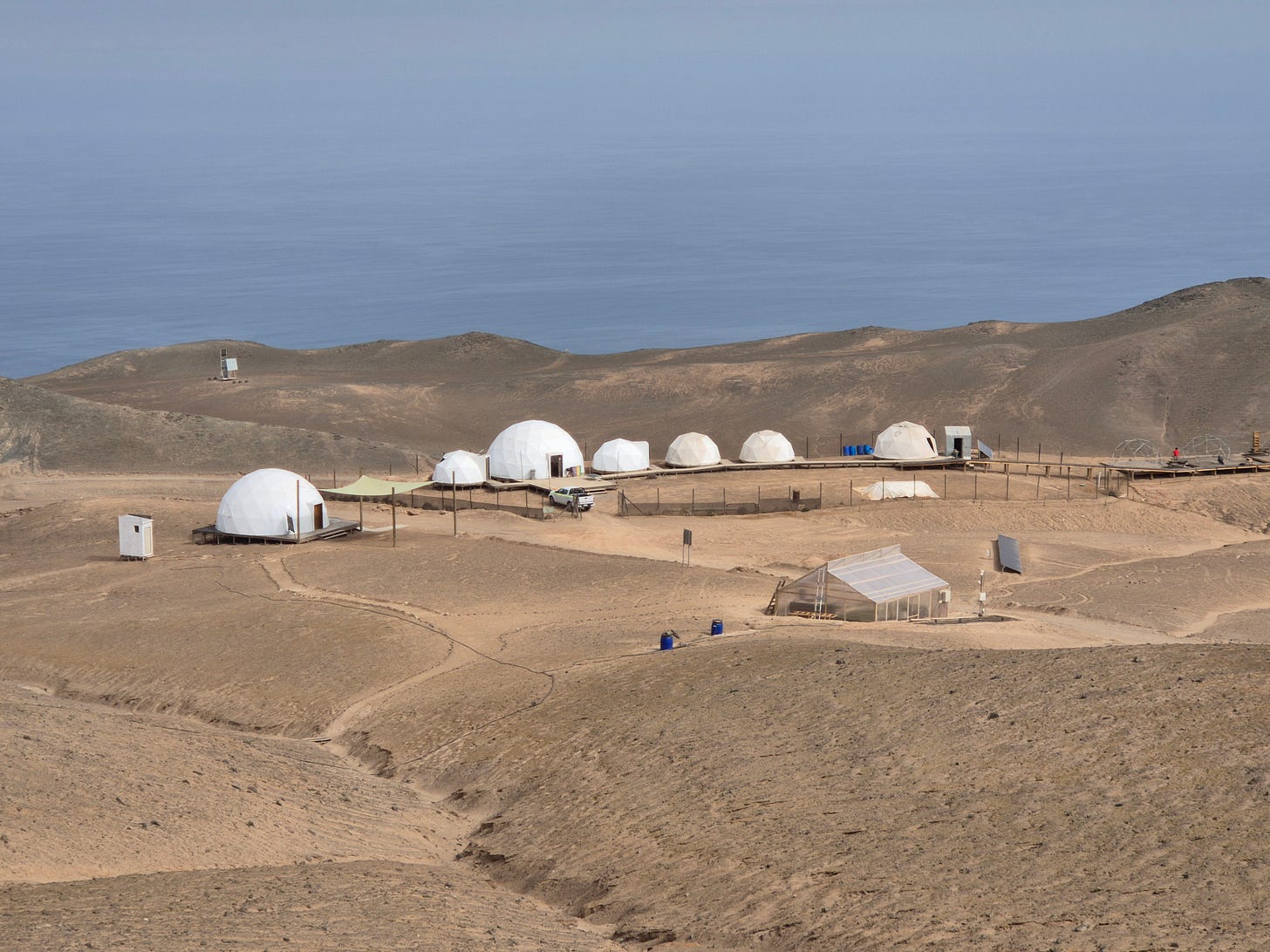

Finally, I made out a cluster of geodesic domes in the darkness. When we got out, a cold wind was whipping through the compound. I could see the Milky Way above my head, but not much else. It could not have been more different from the fluorescent consumer dreamworld of the Zofri mall. This station had been built in 2016, to replace the previous one that had been destroyed by flash floods the previous year.

I was thrilled and disoriented in equal measure, as Milton turned on some electric lights that dimly illuminated the domes and the wooden walkway that connected them. It felt as if I had arrived on Mars, but I had hardly installed myself in one of the domes when I missed my step and fell off the walkway, cracking my forehead on the corner of a nearby bench. Milton was distraught, thinking that I might have concussion, and he had reason to worry. The bench had caught my forehead just above my right eyelid - an inch or two lower and it would have probably crushed the eye.

My first reaction was intense disappointment that I might not see the station the next day. Blood was seeping through my fingers, and I was minded to patch up the cut with a homemade butterfly stitch and tough it out, but when I looked in the mirror I saw the cut was deeper than I thought. So Milton kindly drove me to a polyclinic about half an hour away down the salt route.

Once again we set out into the dark, and veered in and out of the growling trucks. When we got to the clinic, the paramedic gave me the usual tests. I was still dazed from shock and adrenaline, and he made me lie down and asked me what was needed to become a writer. Why would anyone want to do such a thing? He asked, in a concerned, and faintly pityingly tone.

He had a point. But as I lay there with a makeshift plaster on my throbbing head, I tried to defend my chosen profession and explain the qualities required. Surely he must have some stories he would have liked to write about? I asked, hoping to end the interrogation.

He did, and he proceeded to regale me with some tales of unbelievable carnage and tragedy drawn from his long career pulling people from crashed cars and motorbikes along the Iquique-Antofagasta highway. It was almost a relief when he finally told me that I would need stitches, and that we would have to go to Iquique to get them.

So the noble Milton drove me all the way back to Iquique, where a doctor named Doctor Alegre ( Doctor Happy - and no, I’m not making this up) gave me two stitches and sent me on my way at about 4 in the morning. Once again we headed down the highway of death, up the salt route, and onto the dirt road leading into the howling void. Finally, I got a few hours parody of sleep, huddled on a camp bed with the desert winds tugging at the dome.

The next morning, I woke up and looked around at Alto Patache station, and it all seemed worth it. Because this was the desert in all its raw, majestic splendour. From the compound, I could see banks of low cumulus clouds being pushed out to sea by the wind. By mid-afternoon, Milton confidently assured me, the winds would reverse direction, the Camanchaca would descend on the hillside, and the fogcatchers would begin to work their magic.

I left Milton and Jorge assembling another geodesic dome, and walked up the path to the greenhouse and the two largest fogcatchers. I don’t know if it was the blow to my head or the sleeplessness, but I felt exhilarated and even euphoric. To the east, the dry hills stretched out endlessly, and I could see dried up river beds, ancient llama trails, and paleo-runoffs etched like scratch marks into the dry slopes.

At first sight, the terrain seemed utterly barren. But then I saw patches of orange, green and yellow from a distance, and moving closer I could see lichens clinging to the rocks, occasional shrubs, and little pieces of black silicate rock that might have been left by meteorites.

This was not the barren land of The Road or Furiosa. All around me, living organisms had found enough moisture to cling tenaciously to the rocks and dry stony earth, and it was this unlikely capacity for survival that has inspired the UC Desert station and other similar experiments in the Atacama and beyond.

In a hyper-arid region where there is rarely enough rainfall to support human life, Chilean scientists have learned how to extract moisture from the camanchaca fog, which settles for some 1,200 miles of coastline. Fog moisture is not heavy enough to fall to earth and become rain, but scientists saw that lichens and cacti were able to ‘catch’ enough liquid to enable them to survival, and fogcatching technology sought to do the same for humans.

The invention is ingenious and also very simple. Mesh panels are fixed into the upper slopes of the station, which trap moisture as the fog passes through them. These microscopic droplets fall into a plastic gutter, and drain into hosepipes, which connect storage cisterns. When the water in these tanks reaches a certain level, it is transported by high-pressure hose pipes into the station’s sink, showers, and toilets.

Amazingly, this system produces an average of 45,000 litres of water annually - enough to sustain the station and its visitors throughout the year. The water also enables a cactus garden, a greenhouse filled with strawberries, lettuce, tomatoes and herbs, and a small plot of maize. Electricity is provided by solar power, which makes the station - potentially - entirely sustainable.

I felt strangely moved by this experiment, as I stood listening to the wind ‘singing’ through the mesh on the largest fogcatcher. I walked around, examining lichens, past the small fogcatchers, the seismograph that measures tremors and earthquakes, and the meteorological station measuring humidity, temperature, and radiation levels. I saw the ‘art in the desert’ house created by the Catholic University’s architects - the prototype for a sustainable habitation in extreme environments that eventually became a larger house presented at this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture.

At the end of my walk, I stood on the cliff overlooking the salt port at Puerto de , .and the nearby copper port. Further south, I could see the Pabellón de Pica, graveyard of so many Chinese workers who were tricked into slavery to work in the lethal guano industry that provided fertiliser for European and American farmers in the nineteenth century.

Incredibly, it was only 20 years ago - following intervention from the Chinese government- that the remains of Chinese workers who had been left to dangle from the ropes for more than 150 years where they died were finally taken down and given a decent burial.

From guano to copper and salt, this was the history of the Atacama: the ruthless extraction of minerals and metals, from nitrates, silver, copper, and lithium, that have decisively shaped the modern world. The Alto Patache station told another story - a little marvel of human adaptability with implications for Chile and beyond.

At one point in my wanderings, I came across a large bush that seemed to owe its existence entirely to the fogcatching cistern alongside it. Rising up out of the stony ground at a height off nearly four feet, it seemed nothing short of miraculous.

But there is no miracle here - just scientists using their intelligence and knowledge to solve local problems that are also global problems. This is why Carlos Espinosa, the Chilean scientist who first invented fogcatchers in the 1950s to address the problem of water scarcity in Antofagasta, donated his patent to UNESCO, so that others could use it. The Alto Patache station has been instrumental in creating the AMARU (water snake in Quechua) ‘Fog Catcher Map’ which uses data from the 25 stations of the Chile Fog Water Monitoring Network.

As Milton told me, fogcatching is not a catch-all solution to hyper-arid spaces. Not every desert has the regular fogs that descend on coastal Chile, or the coastal cordillera that prevent them from dissipating, and the winds that push the camanchaca into the traps. But in demonstrating human adaptation to an environment that is generally considered to be unsuited for human habitation, it also offers a relatively low-tech micro-solution that could potentially be applied to other countries with similar conditions.

In the years to come, we will need this kind of ingenuity and creativity, and altruistic science. Last week the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) delivered another of its increasingly grim warnings on global desertification and drought. Coming in a summer when even Europe is sweltering under record-breaking temperatures, the report was further confirmation that desertification is part of our present and future.

By the late afternoon, the Camachaca had not appeared, and I was amazed to count four drops of rain on my face and hands. Milton and Jorge eyed the clouds gloomily, and said that there would be more where that came from.

It didn’t seem likely, but as I drove back to Iquique, I felt encouraged and hopeful by what I had seen. In the future we will need the fogcatchers far more than we will need Mad Max and Bartertown. In a world facing ecological catastrophe, we will need people looking for practical, accessible solutions to natural problems and the problems that humans, and not for profit or glory, or the benefit of shareholders, but to help others.

As we approached my hotel, a man dressed as Predator was pretending to attack passing cars. It seemed a fitting end to my wild ride into the desert. Once again, I thanked Milton, who had done so much to help me. And as I walked into the hotel lobby, the privilege of seeing this experiment with my own eyes was well worth the crack on the head.

Milton and Jorge were right, of course. That night it rained in Iquique, Alto Patache and in other parts of the Atacama. Such events do happen from time to time, but they are never enough to make a long term difference.

This is why the fogcatchers are needed. And in the years to come, many Chileans in the north will be keen to see how Amaru the water snake wends its way up and down the coast, and other communities around the world may also have reason to see how this experiment unfolds.

All photographs taken with permission of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Norte.

In Namibia there is a desert beetle that is similarly able to trap moisture from the fogs that roll in from the Atlantic. I wonder if the scientists had made a connection…