In my last letter, I described the Atacama Desert as a repository of memory; a blank canvas, on which the names of the dead have been written in order to ensure that their names are not forgotten. These aspirations are not limited to individuals. Drive nine miles from the city of Calama, through the rubbish-strewn desert and the forest of whirling wind turbines that line the road to San Pedro de Atacama, and you will notice a tall white cross protruding from the entrance to a circle of twenty-six round pink pillars.

It isn’t till you drive off the road leading to this ‘Park for the Preservation of Historical Memory’, that you realise how large and imposing it is. The monument was inaugurated in 2004, at the same place where the remains of 26 political prisoners murdered by the Chilean army in October 1973, were found 19 years later in 1992.

We visited the monument yesterday evening, and descended the steps to the circle of bare earth baring flowers and tributes to the men whose remains were found in this same spot. At the centre of the circle, a brass plaque from the Group of Family Members of the Politically Executed and Disappeared Detainees’ (AFEDDEP) of Calama paid tribute to the 26 men who had been buried in ‘the dry soil of Atacama’ in this same spot. The monument lalso recalled the relatives of the victims who had engaged in a ‘long search through the desert that is still not over.’

The monument - and the time cycles it incorporates - marks one of the most notorious crimes carried out by the Pinochet dictatorship, and it’s also a testament to the long struggle for recognition and justice waged by a group of women from Calama, and one woman in particular: Violeta del Rosario Berríos.

I first heard of Violeta nearly seventeen years ago, in Patricio Guzmán’s great film about the Atacama Desert, Nostalgia for the Light. Until then, I knew nothing of the women of Calama, who had spent decades searching through the desert for bone fragments of their husbands, sons and brothers who were murdered by the Pinochet dictatorship in 1973.

Naturally, the dictatorship never admitted to these crimes, nor did it tell the relatives of its victims where the bodies of their loved ones could be found. Because, like the other military regimes that seized control of the southern cone countries in the early 70s , the Pinochet dictatorship was cunning, cowardly and cruel in equal measure. In granting itself impunity for whatever crimes it felt the need to carry out in the name of anti-communism and ‘national security’, the regime frequently resorted to the sinister tactic of ‘forced disappearance’, and the Atacama was one of the regions of Chile where these bodies were dumped.

When I saw Gúzman’s film, I was shocked and moved by what seemed like some awful Greek torment - a terrible exercise in futile suffering that Odysseus might have inflicted on the Trojan women.

In the film, Gúzman lets Violeta Berríos do most of the talking. At one point, she delivers a heartfelt monologue to camera in the middle of the desert that is one of the rawest and most searing expressions of grief and loss that has ever appeared on a cinema screen. Gúzman’s film was made in 2010, and Violeta’s face is a mask of agonised intensity, leathered and lined by the decades that she had spent combing the desert in search of her husband’s remains.

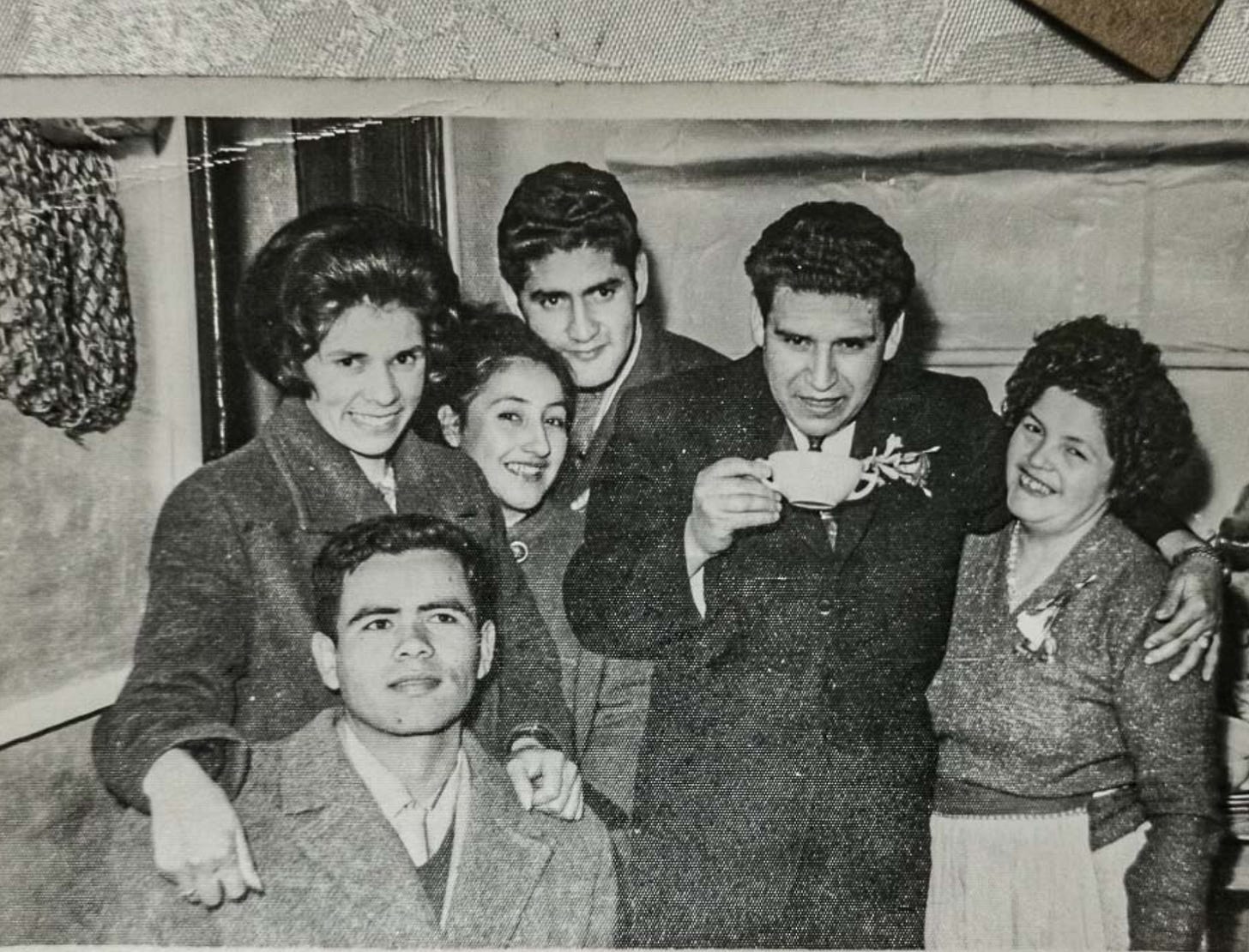

The day before my visit to the monument, I visited Violeta in her little house in the mining town of Calama. She is now 87, frail, slow-moving, and clearly in poor health, as she came to the gate in her dressing gown and slippers, and shushed the two rowdy dogs that she calls her ‘daughters.’ This is the same house that she once shared with her husband Mario Arguelles Toro, a taxi-driver and local Socialist Party member in Calama. In the photograph below, she can be seen in the left, standing with her hands on his shoulders.

At that time, Violeta ‘knew nothing about anything’, as she puts it, and lived a peaceful domestic life with her idealistic husband. That world came crashing down on 19 October 1973, when a special unit which later became known as the ‘Caravan of Death’ arrived in Calama in a Puma helicopter, to carry out the last phase of a campaign of murder and extrajudicial executions which would ultimately leave 75 people dead in the Chilean north. This unit was lead by General Sergio Arellano Stark, a fanatical anti-communist and close confidant of Pinochet, and effectively acted as a state-sanctioned death squad, killing prisoners who had already been sentenced to imprisonment on trumped-up charges relating to their political affiliations to Allende’s Popular Unity movement.

Before Arellano’s arrival, many of these prisoners believed that they were about to be sent to concentration camps in the south. Arellano’s unit had other ideas. Because of Calama’s connections to the copper industry and the Chuiquicamata mine, the city was considered to strategically important to the regime and singled out for a special dose of exemplary terror.

Overruling or imposing his own mandate on local commanders, Arellano’s unit had already established spurious ‘war councils’ across the north, that sentenced prisoners to death merely for membership of the Communist or Socialist parties, and it proceeded to do the same in Calama.

Such behaviour shocked even the commanders who had arrested these prisoners in the first place. The commanding officer who received Arellano’s men in Calama with a marching band and an honour guard, was shocked to find the general’s unit draped with cartridge belts and carrying machine guns in a state of combat readiness. Arellano immediately called a war council, and his men set about beating the prisoners and selecting names for execution. By the end of the night, 26 men had been shot and cut to pieces with sabres, and buried in the desert.

One of them was Violeta’s husband Mario. And his murder plunged her into a political nightmare that has never really ended. In November 1973, she joined the Socialist Party. That same month, she joined the Chilean Commission of Human Rights, beginning a long trajectory as a human rights campaigner, which has earned her both national and international recognition. Violeta was a founder member of AFEDDEP, which lobbied successive Chilean governments to find the remains of their loved ones, and bring those responsible to justice.

Year after year, week in, week out, Violeta and the women of AFEDDEP combed the desert in search of their disappeared relatives. Supporting herself as a cleaner, Violeta and her compańeras went out into the desert whenever they could. They began their search at a time when the Pinochet regime was at its most savage and dangerous, and they continued to search throughout the dictatorship years and beyond. It was not until July 1990 that the women of Calama were directed to a mass grave containing the remains of 24 of the 26, including a single bone that belonged to Violeta’s husband.

This was not the original spot where the men had been shot. Like its counterparts in Argentina, the dictatorship constantly tried to cover its tracks, and so the 26 had already been dug up and reburied in the spot where they were found - a process which further destroyed their remains. After years of searching, Violeta and her companions were shocked to find that the remains of their menfolk had been buried only a hundred yards from the main road.

Even then, the women continued their search, because, as Violeta once said, they wanted more than a single bone fragment, and also because the grave contained the remains of only 24 of the original 26. In 2008, Arellano Stark was sentenced to six years in prison for his role in the Caravan of Death - a mockery of justice that he escaped on grounds of dementia. He died in 2016, without serving time.

The Eternal Walker in the Desert

Today, the woman who once described herself as an ‘eternal walker in the desert’ is not longer able to scour the Atacama, but she has never really left the desert. Some years ago she told an interview that she had ‘no life beyond the search. ’ I asked her if she still felt like that. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘ Because I realise what the doctors once told me a long time ago, that these are the consequences of everything that happened. They said that you have to cut this cord and live the little life that remains to you. But I live here alone with my dogs and cat. I live mentally in the desert. The desert is always here in my home.’

Had she never felt any temptation to abandon the search or give it up during those years? ‘When I reached sixty,’ she said, ‘I didn’t realise that thirty years had passed. I didn’t notice it. It’s cost me so much effort to come to terms with this, because those thirty years - did I live them? I don’t know how I lived them. The only thing that existed was the desert.’

For some people, who have not undergone the experience of forced disappearance, I suggested, such tenacity would be difficult to comprehend. Where did she think it came from? ‘Honestly, I don’t know,’ she replied. ‘You can’t tell where it comes from. One day we began to go out searching and that’s how we found ourselves. But I can’t explain to myself where it comes from, this desire to have some trace, to find something, even when I never thought I’d find even a rib.’

Violeta still has very clear memories of the husband she lost. She described Mario as a ‘calm man who was very easy to talk to’, and remembers he and his friends trying to ‘put the world to rights’, and discussing political issues that she had no interest in at the time. When I asked her why she joined the Socialist Party only a month after his death, she said that she simply wanted to ‘keep his flag flying.’

Perhaps not surprisingly, after everything she has gone through, she now declares herself to be ‘disillusioned with politics and everything’ in her own country, and is pessimistic about the impact of her years of campaigning on present-day Chileans. She listed some of the massacres and crimes carried out by the Chilean army in the past, and clearly saw the potential for their repetition in the future. ‘We Chileans have a very short memory,’ she said. ‘We don’t look back too far. So I hope that no one will ever have to go through what we experienced. To read about it is so much easier than living it. You would not want anyone to go through a situation like this, to search for a man, your brother, your husband.’

I agreed. And as I sat in the living room of this brave, exhausted, but indomitable woman, I imagined Mario talking to his friends about putting the world to rights, when he and so many other Chileans believed they had discovered a democratic path to socialism. I thought of the proud, happy, smiling woman in that youthful photograph, and imagined the life Violeta might have had, if her husband had not held those beliefs. Perhaps Mario would have grown old with her, living in that house with their dogs and cat, visited by their children and grandchildren.

Instead, their lives had been wrecked by fascism, and the cruel barbarities of twentieth century politics. It was easy to see Violeta and her friends as victims, driven by a grief that was close to madness as they combed the desert for the remains of their loved ones.

But what I saw in the gaunt, shrunken woman beside me was an astonishing courage that led her to challenge a state that had turned serial killer and murdered the citizens it was pledged to protect; a deep, unshakeable devotion that refused to allow the man she had loved to be erased from the earth, and a powerful bond of solidarity that connected her to the other women of Calama, when others might have walked away.

Joan Baez once said of the Mothers of the Playa de Mayo, that the human race would have disappeared centuries ago had it not been for women like them. The same could be said of Violeta and the other eternal walkers in the desert. When our conversation was over, she gave me a badge from AFEDDEP Calama, which read, ‘If I am in your memory, I am part of history.’

As I left, I hugged her, and holding her delicate, fragile body in my arms, I murmured that it was a privilege and an honour to have met her, because it was. And stepping out into the sunlight to catch a taxi, I knew that she would always be in my memory, but I wished she, and so many others, had been part of a different kind of history.