Following last week’s post about the 2015 sex attacks in Cologne, I’m recycling another post on the same subject that I wrote a month later, critiquing the brilliant Algerian writer Kamel Daoud’s controversial take on those events.

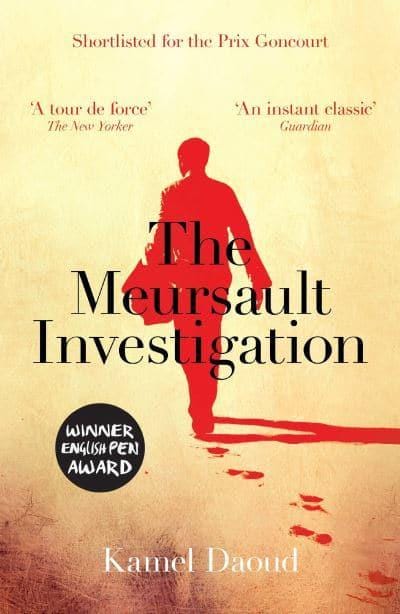

I’m a big fan of the Algerian novelist Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation, which I read last year. It’s a stunning deconstruction of L’Etranger, which brilliantly imagines the voice of the Arab colonial subject that was missing from the Camus’s novel. In doing so, it invites Camus’s readers to re-think the essential assumptions of a novel generally considered to a triumphant expression of 20th century humanism, and exposes the narrow prism through which Camus viewed colonial Algerian society, and which reduced its non-French members to props and bystanders in a supposedly universal existential fable.

The result is a combination of homage/critique and an essential companion piece to Camus’s classic, which fuses a profound meditation on the impact of French colonialism and French culture on Algerian society with an equally unsparing overview of the failings of post-colonial Algerian history, from the War of Independence to the Islamist surge of the late 1980s and the bloody civil war that followed.

To have achieved all this in 160 pages is no mean feat. It’s fearless, moving, and audacious. All the more disappointing therefore, to read Daoud’s response to the Cologne sex attacks in the New York Times last week entitled ‘The Sexual Misery of the Arab World.’

To say that Daoud’s article is not helpful doesn’t really begin to describe it. Where The Mersault Investigation challenged prejudices and received ideas, Daoud’s take on the Cologne attacks reinforces clichés, stereotypes and assumptions that routinely emanate from people far less intelligent than he is.

The ‘Arab Sickness’

Daoud’s essential premise is that the attacks on Western women by Arab migrants in Cologne, Germany, on New Year’s Eve were an extension of the assaults and harassment of women that took place in Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the heady days of the Egyptian revolution. In reminding Westerners of these assaults, Daoud argues, the events in Cologne have led people in the West to realize that one of the great miseries plaguing the Arab world, and the Muslim world more generally, is their ‘sick’ relationship with women.

Daoud rightly attacks the brutal absurdities resulting from fundamentalist sexual repression in Algeria and other Arab countries, and the morbid obsession with female sexual behaviour at the heart of it. But his notion that what happened in Cologne was a product of a uniquely Arab sexual pathology seems oblivious and even indifferent to what actually took place, or to the utterly spurious interpretations placed on the horrific events of New Year’s Eve by commentators who had no interest in establishing what actually happened that night.

When news of the Cologne attacks first broke, they were initially blamed on refugees, and on Syrian refugees in particular. Across Europe Cologne was cited by the far-right as evidence of the cultural and civilizational incompatibility of Europe’s refugees, or the product of ‘Arab’ or ‘Muslim’ savagery.

In newspaper op eds, on Twitter and across the Internet, the outrage at the treatment of ‘our’ women was often combined with a gleeful we-told-you-so condemnation of Europe’s ‘bleeding heart’ liberals, who had supposedly led these savages into the metropolis only to be hoist by their own petard.

In some European cities, this outrage spilled into perverse acts of ‘chivalry’, in which fascists and motorcycle gangs established vigilante groups to defend European womanhood by attacking anyone who looked like a refugee.

The Cologne attacks also produced a special kind of 'cultural commentary, such as this ‘satirical’ image from Charlie Hebdo:

In some German cities local authorities handed out leaflets informing refugees how women should be properly treated. I suspect that the men who carried out the attacks in Cologne know perfectly well how women should be treated – they simply chose to ignore these norms, as some men will do pretty much anywhere when they get the chance.

Daoud however, sees these events as a product of a unique and explosive collision between the repressed and forbidden desires of the Middle East and the continual orgy that takes place in the liberated West. Why? Because

Paradise and its virgins are a pet topic of Muslim preachers, who present these otherworldly delights as rewards to those who dwell in the lands of sexual misery. Dreaming about such prospects, suicide bombers surrender to a terrifying, surrealistic logic: The path to orgasm runs through death, not love.

Of course it does. And Daoud also seems to believe that the path to orgasm runs through Cologne Central Station. Never mind that Cologne was not quite what it seemed to be, let alone what it was portrayed as being.

According to the Cologne public prosecutor, only three of the 58 suspects arrested in connection with these attacks were refugees. In addition, 600 out of 1000 reported incidents that took place in Cologne on New Year’s Eve were related to theft, and were not sexual attacks. That still leaves 400 incidents that were sexually-related, so we are still dealing with a major incident of sexual violence and harassment perpetrated mostly by men of Middle Eastern or North African origin.

But that does not support Daoud’s crass notion of a cultural and civilisational clash that comes straight out of the counterjihadist playbook:

… today with the latest influx of migrants from the Middle East and Africa, the pathological relationship that some Arab countries have with women is bursting onto the scene in Europe. What long seemed like the foreign spectacles of faraway places now feels like a clash of cultures playing out on the West’s very soil. Differences once defused by distance and a sense of superiority have become an imminent threat. People in the West are discovering, with anxiety and fear, that sex in the Muslim world is sick, and that the disease is spreading to their own lands.

Tommy Robinson and Pegida couldn’t have put it better. Neither they – nor Daoud – seem to care that this ‘disease’ was already present before the refugee hordes came here. As I’ve argued in a previous piece, women have been subjected to sexual harassment, rape and the threat of rape in liberated Europe for a long time. Many women in Europe continue to experience ‘anxiety and fear’ at the hands of men on a daily basis. German women are regularly assaulted at the Munich beer festival, amongst other events, yet such things only ever seem to become politically important when Arabs or Muslims are responsible.

Daoud’s intervention is no exception. He notes that ‘ The West has long found comfort in exoticism, which exonerates differences’, yet he himself merely reinforces spurious notions of cultural difference and incompatibility that are already reflected in magazine covers like this one:

That cover ‘exonerates differences’ alright, even as it references long-established cultural tropes about white women being sexually molested by brown-skinned savages as a kind of metaphor for the ‘Islamic rape of Europe.’ Daoud seems uninterested in why such things happen.

Where the likes of wSIECI have used the Cologne attacks to recycle racist imagery, he has used these attacks to support the notion of a cultural clash between a ‘sick’ Arab world and a sexually-liberated West.

It’s shallow, crude, and dangerous stuff. In The Meursault Investigation Daoud was an unsparing critic of colonial and post-colonial Algeria. Here he acts like the classic ‘native informant’, telling a Western audience what too many of its members already like to believe about themselves – and about the others who can never be like them.