Godzilla Minus One

Why Fictional Destruction Can Never Keep Up With the Real Thing

I’m not particularly fond of monster movies. I tend to find them tedious and repetitive, and special-effected mega-destruction based on CGI and Dolby screams and growls make me feel as if I’ve spent two hours - and they are rarely shorter than two hours - at the fairground. In the past I have made exceptions, such as Alien and Predator, but even these monsters eventually became tedious and predictable.

So generally-speaking, this is not a genre that I like to spend money on. Nevertheless, I went to see Godzilla Minus One just before Christmas on my daughter’s recommendation, and she wasn’t wrong. It’s surprisingly moving for a monster film, partly because of the touching performances of its vulnerable lead characters: the haunted kamikaze pilot Koichi and the ‘wife’ Noriko with whom he shares the parenting of the utterly charming wartime orphan Akiko, as he finds his way towards heroic redemption, by saving his city from the rampaging radioactive and seemingly indestructible Godzilla.

The support performances are also really affecting; the acting and the facial expressions of even the most minor characters are so expressive that they might have been faces in an Eisenstein movie - I mean they could tell the entire story without making a sound.

I liked the comic-book aesthetic, and I particularly appreciated the sombre references to Japan’s wartime past, not only in terms of its impact on the central characters, and in the film’s recognition of Japan’s exploitation of its soldiers and airmen, and the visual continuities between the destruction of Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the skilfully-filmed devastation inflicted by Godzilla.

These metaphorical references are what makes Godzilla different from most cinematic monsters. Unlike King Kong, this is a creature with no anthropomorphic touches to make it even vaguely relatable or sympathetic. It hasn’t been wronged or cruelly treated. It’s not even cruel, like Alien or Predator. It hasn’t been tormented, like Bruce Banner/The Hulk. It’s not an alien species, or a dinosaur breaking out of a national park. It’s a maniacal human creation, empowered by human experimentation with weapons of mass destruction, which have given Godzilla its radioactive powers, but it has no motivations, appetites or goals, beyond its desire to lay waste to everything in its path.

In this sense, Godzilla is a form of psychological projection - an externalisation of humanity’s destructive capacity. It has the powers that we have given it, and it shows how ephemeral and fragile our societies are, as it wreaks destruction on our cities, transport systems, theatres, libraries, and all the other components that hold urban life together. The monster is immune to the worst we have done and the worst we can do to it. Bombs, bullets, and shells bounce off it or only succeed in enraging it further, exactly as they did did in the original.

This capacity for destruction is also part of Godzilla’s fascination. And the ease with which it tramples buildings and swats away planes and missiles like toys expresses anxieties regarding the possibility of apocalyptic end-times collapse that can be traced all the way back to the Book of Revelation, or Bruegel the Elder’s The Fall of the Rebel Angels:

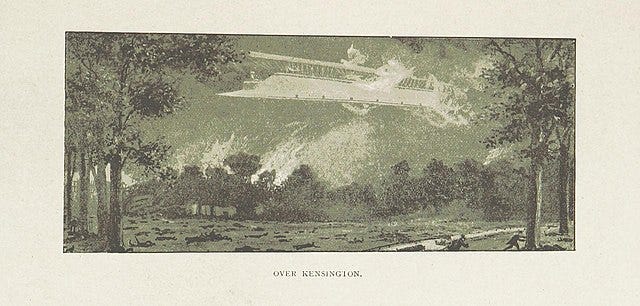

These same fears have continued to percolate through the modern imagination, amplified by the development of modern weaponry, whether it’s the anarchist-terrorists of the 19th century illustrated novel Hartmann the Anarchist, who blow up London from a zeppelin:

Or HG Wells’ The War of the Worlds:

And these fears were realised, not by anarchists or aliens, but by the destruction of cities by national armies during the 20th century, in World War I at Ypres:

Or Hamburg in World War II:

At Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and also in the firebombing of Toyko - the single most destructive aerial bombardment in history - where more than 100,000 people were killed in a single night by incendiary weapons that were specifically designed to burn the wooden houses where most of Tokyo’s population lived.

No wonder these visions of total destruction have haunted the Japanese imagination, whether in the photographer Hisaharu Motada’s ‘neo-ruins’ series on post-apocalyptic Tokyo:

Or the video game and anime artist Tokyo Genso:

Godzilla was, and is, another fictional expression of real wartime trauma, in which humans did exactly what Godzilla did. They reduced entire cities to rubble, destroying homes, parks, libraries, town halls, museums, galleries, bars, clubs, trains and train lines. They attacked cities and the people who lived in them in order to realise military and political objectives. And watching Godzilla trash Japanese cities, I couldn’t help thinking of what modern armies have done to Aleppo:

And Mariupol:

Or Gaza:

All of this has been ordered, approved or carried out by men and women in suits and uniforms, by hard-faced authoritarians like Netanyahu and Putin, by Assad - the former ophthalmologist who signs off letters to his wife with ‘love U’ - by yawning drone operators, by scientists and technicians, by op-ed columnists and liberal presidents - all of whom accept, embrace or defer to the unacknowledged rule: that war is no longer fought between armies on the ‘battlefield’, but by directing various forms of military force against civilians and non-combatants.

All this is well-known and widely-accepted. Yet the same governments that designate ‘non-state actors’ who carry out such acts as terrorists, reserve the right to attack neighbourhoods and cities in the name of ‘wars on terror.’

And at the end of this bleak year, as the enraged Israeli Godzilla grinds the Gaza Strip to rubble, destroying parks, libraries, hospitals, schools, and community centres, we would do well to remember that human beings have created real scenes of devastation and desolation that can equal anything our fictional monsters can deliver, where, as Federico García Lorca once wrote, ‘The dead decompose under the clock of the cities/war goes goes crying with a million gray rats.’

You sense, watching Godzilla Minus One, that its director Takashi Yamazaki knows this too. At the end of the film one of the characters asks the hero-pilot if the war is finally over for him, to which he replies in the affirmative. And beyond the thrills and entertainment, you can’t help feeling that the movie’s director would like the war to be over for us too.

"All of this has been ordered, approved or carried out by men and women in suits and uniforms, by hard-faced authoritarians like Netanyahu and Putin, by Assad"

Probably worth noting that it has also been approved, aided and abetted by a number of leaders of our "western civilisation" like Biden, Bush, Blair, Sunak and a host of others and that, in a lot of instances, it could not actually have been accomplished without the assistance, (e.g. the US military stockpile in Israel), provided by the west, acting in function of its shared commitments to democracy, social ethics, humanity and the much-touted christian values of compassion and peace.

Now nominated for an Oscar.