In an age haunted by catastrophes, it’s not surprising that the twenty-first century has become the golden age of dystopian fiction. Zombies; post-apocalyptic urban collapse; machines replacing humans; pandemics, plagues; the enslavement of women; pervasive surveillance; police states and martial law - the worse things get the more we lap them up, and the more we use dystopias as reference points that help us interpret - or fail to interpret - our own times.

Are we 1984 yet? Are we Big Brother, Brave New World, or Black Mirror?

And now, hot on the heels of HBO’s The Last of US, Netflix has transformed the Argentinian series The Eternaut into the latest dystopian sensation. The series is based on the science fiction comic strip El Eternauta, created by the Argentinian comic writer Héctor Germán Oesterheld in the late 1950s. The original story was told by a ‘navigator from the future’ named Juan Salvo, who visits Oesterheld in a homemade diving suit to recount an alien invasion that begins when the population of Buenos Aires is decimated by a toxic snow storm.

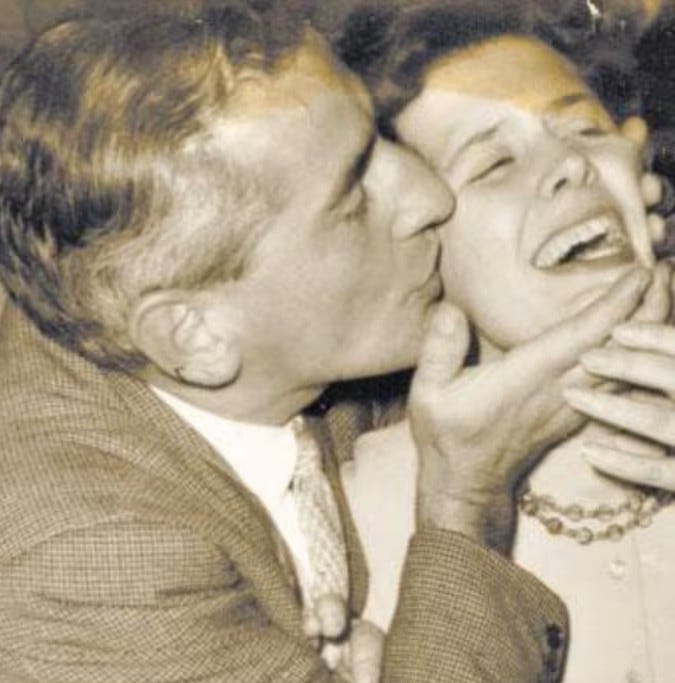

The strip was published in 1957, only two years after the military coup that overthrew Juan Perón, and was sometimes interpreted as an allegory of military rule. Oesterheld explained how he set out to create a kind of futuristic Robinson Crusoe, after imagining his own family ‘suddenly alone in the world, surrounded by death and by an unknown and unreachable enemy.’ This is a picture of Oesterheld and his wife Elsa, probably taken in the 1950s.

At that time, Oesterheld was a geologist and budding comic strip writer, who was sympathetic to the exiled Perón. By the end of the decade he was the father of four daughters, and El Eternauta had become one of the country’s most popular comic strips.

Throughout the sixties, Oesterheld continued to support the banned Peronist movement, even as he gained international recognition for comics that included biographies of Evita Perón and Che Guevara. In the early 1970s, he and his four daughters joined the leftwing Peronist revolutionary movement Montoneros. Like the crime novelist and investigative reporter Rodolfo Walsh, who followed a similar trajectory from writer-activist to middle-aged revolutionary, Oesterheld was his fifties when he joined Montoneros as a press officer.

The Maelstrom

Oesterheld’s wife Elsa later recalled how she warned her ‘very disingenuous’ husband that he was making a ‘grave error’. Señora Oesterheld described her husband as ‘a philosopher who forgot the practical world. He gave in and adhered to violence because he thought that there was no other way to change things.’ After two decades of military rule, many young Argentinians felt the same. Even after Perón returned from exile in 1972, following an agreement with the military, Argentina was engulfed by a vicious cycle of revolutionary and counter-revolutionary violence.

Though Señora Oesterheld urged her husband to protect their daughters, their fate was out of his hands. In 1976, the Argentine armed forces overthrew the government of Perón’s widow Isobel, and began the program known as ‘el proceso’ - the Process of National Reorganization.

Blending the Nazi doctrine of ‘Night and Fog’ with counterinsurgency techniques borrowed from French military veterans of the Algerian War who advised the military high command in the 1960s, the military junta set out to exterminate Argentina’s revolutionary generation, through an unacknowledged campaign of kidnapping and murder.

In this so-called ‘dirty war’, revolutionaries, priests, nuns, social workers and high school children were kidnapped, tortured and shot, or drugged and thrown alive from airplanes and helicopters into the sea.

The Oesterhelds were quickly sucked into this maelstrom. In June 1976, Oesterheld’s nineteen-year-old daughter Beatriz was kidnapped, on the same day that she told her mother that she intended to leave Montoneros and dedicate herself to medicine, so that she could work ‘in the jungle, like Che, or in the barrios (poor neighbourhoods) where the people really needed her help.’

In August, the twenty-three-year-old Diana Oesterheld was kidnapped and taken into captivity while pregnant. Oesterheld evaded capture until April, 1977. In November that year, his pregnant daughter Marina was captured. And in December his daughter Estela and her partner were shot dead in a gunfight, leaving their three-year-old child Martín, who -unusually for those times - was handed over to the family.

Of the four daughters, only the body of Beatriz Oesterheld was returned to her mother. To this day, the fate of Oesterheld and his other three daughters remains unknown. Along with some 30,000 Argentinians, they were subject to the hideous strategy of ‘disappearance’ which enabled the Argentinian state to dispose of its victims with complete impunity, while publicly denying any responsibility for these events.

These are Oesterfeld’s daughters. There are faces like these all over Argentina, on murals and other spaces of remembrance of men and women mostly in their late teens and early twenties, some of whom are even younger. These images were taken in happier times before they became ‘chupados’ - the sucked ones - when most of them were still living the lives of their generational peers.

The military did not photograph its victims. From the moment they were captured, they vanished from the world, and this is what happened to the creator of El Eternauta. A psychologist detained by the military later provided one of the few glimpses of the man who detainees called ‘el viejo’ - the old man, in captivity:

The guards gave us permission to take off our hoods and smoke a cigarette. They also allowed us to talk to each other for five minutes. Then Héctor said that as he was the oldest he wanted to shake hands with all the prisoners present, one by one. I will never forget that handshake. Héctor Oesterheld was sixty years old when this happened. His physical condition was very bad indeed. I don’t know what happened to him. I was freed in January 1978. He stayed in that place.

Despite calls from Amnesty International and other organisations for his release, Oesterheld was never seen alive again. Elsa Sánchez de Oesterheld survived the massacre of her family and joined the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. In an interview with La Nación before her death in 2015, she declared, ‘I don’t know who I am, nor how I am alive, because everything I have been has gone.’

The regime that murdered the Oesterhelds claimed to be fighting a war on behalf of ‘Western civilization’ against an international communist conspiracy. Some army officers believed in ‘Plan Andinia’ - a crazed anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that Israel intended to establish a Jewish state in Patagonia. Fuelled by hatred and paranoia, these defenders of civilization tortured entire families in front of each other, and violated every principle of justice, morality and mercy. Most of them have have never been charged, and are now slipping quietly into the old age that they denied their victims.

Those who defend such actions - and there are many that do - argue that Montoneros were not victims, but members of a revolutionary organization that executed hostages, killed soldiers and police, and set off bombs. All these things are true, but nothing Montoneros did justifies what was done to them and to so many others who were not armed revolutionaries or even members of revolutionary organizations.

As Argentina’s National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP) observed, the violence unleashed by the regime was infinitely worse than the violence it was supposedly intended to eliminate. During the first trial of the military junta in post-dictatorship Argentina, one of the relatives of a ‘disappeared’ former guerrillero asked why her son had not been put on trial, and the same question can be asked of every single person murdered by the dictatorship.

Not for the first or the last time in history, ‘terrorism’ became the pretext for the abandonment of all legal norms, and enabled the Argentinian state to behave, effectively, like a serial killer.

In Argentina, the slogan adopted by CONADEP and proclaimed by the state prosecutor Julio César Strassera at the 1985 junta trial was ‘nunca mas’ - never again. Today, the government of Javier Milei and his dogmatic vice-president Victoria Villaruel - a longtime campaigner on behalf of the military officers she regards as unjustly imprisoned political prisoners - is actively undermining the policy of remembrance established by its predecessors, and reportedly seeking to place some of the imprisoned repressors under house arrest, and even free them.

These developments are unfolding at a time when military regimes and dictatorships across the world continue to inflict lawless violence and repression on their citizens, often using terrorism as the pretext. Even democratic governments are increasingly embracing authoritarian, autocratic and fascistic forms of governance.

In Gaza, Israel is inflicting genocidal levels of violence, mass starvation and ethnic cleansing on a defenceless population, with the complicity of liberal governments that proclaim a common commitment to human rights and international law.

Such commitments no longer apply even in principle in Trump’s America, where immigration police arrest toddlers and ship migrants to prison/concentration camps with no legal accountability. Only last week, Trump’s ghoul-like advisor Stephen Miller announced that the government might soon suspend habeas corpus - the cornerstone of any constitutional defence against unlawful detention, which the Argentinian dictatorship also abandoned.

It is against this background that The Eternaut is now streaming - another testament to our seemingly insatiable appetite for visions of the worst possible future. And as viewers across the world contemplate director Bruno Stagnaro’s brilliantly-realised post-apocalyptic Buenos Aires snowscape, few remember the not-very-distant past, when the dreamy comic strip artist who loved westerns, aliens and war comics was murdered by his own government, along with his four daughters.

When Oesterfeld created his hero Juan Salvo and his companions who do battle with giant bugs and Invasion of the Bodysnatchers-style alien pods, he was already fascinated by questions of collective and individual heroism, resistance and solidarity.

We cannot know whether these same concerns transformed him into the middle-aged revolutionary who continued to write comics even in captivity. But the terrible fate of the Oesterhelds is a reminder that humans have the capacity to create dystopias that are far worse than the imagined futures we watch for entertainment. And in our new age of monsters, it is incumbent on men and women of good to resist the political forces that are once again threatening to plunge their countries into fanaticism, cruelty and fascistic madness.

A very powerful piece - thank you Matt. There have been lots of recent references to Orban, Modi, or Erdogan but there are clear lessons from Argentina which people maybe less familiar with. And recall the deep involvement of the USA and its security services. This was a very wealthy country in the first part of the 20th Century that has struggled with various forms of autocracy ever since. On the watchlist.

Another series to watch has been Families Like Ours which tackles the linked issues of climate change and refugees. Showing how even in supposedly sophisticated European countries, once wealthy people can be become disposed and then treated with hostility by their neighbours.

Thanks Matt. Fascinating and shocking stuff