Conservation and sustainability are not concepts that come easily to an industrialised and largely urbanised civilisation that has tended to regard the natural world as a free gift ‘that ‘can be taken without repayment’, as the political theorist Alyssa Battistoni puts it.

The great nineteenth century Arctic scientist, writer, and prolific whale hunter William Scoresby once commentated on the great abundance of little 'slime fish' (Acalephae) sometimes known as medusae that attracted whales to Svalbard/Spitsbergen to feed on them. In Scoresby’s estimation, this feeding chain was another manifestation of the ‘ Providence of God’, which enabled whales to ‘ fall victims to the prowess of man’ and thereby ‘ rendered subservient to his convenience in life.’

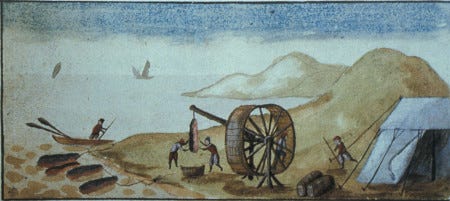

This belief that certain animals existed purely for the ‘convenience’ of humanity was often accompanied by a refusal to believe that such resources were not limitless. Between 1615- 1820 whales in Svalbard were so systematically slaughtered that whaling virtually ceased in the region, and hunters moved on with equal ruthlessness through other Arctic species, from walruses and seals to reindeer, foxes and polar bears.

The nineteenth century Scottish explorer and sportsman Sir James Lamont witnessed an episode in Svalbard in which sixteen walrus hunters attacked walruses with spears, until 'the passage to the shore soon got so blocked up with the dead and the dying that the unfortunate wretches behind could not pass over and were in a manner barricaded by a wall of carcasses.'

Each of these walruses, according to Lamont, was worth twenty dollars, and for most of the local hunters who killed them for sale on markets outside the Arctic their immediate economic value was the only value they had.

Other hunters shot Svalbard’s mammals for sport. King Albert I of Monaco (1848-1922) led four scientific expeditions to Svalbard, and denounced ‘certain tourists whom cruise ships or yachts bring north’ who ‘derive a stupid pleasure from shooting hundreds of inedible birds, reindeer whose carcasses are left lying, and seals whose bodies sink to the sea-bed.’

Whether killed for sport, sustenance or profit, the history of the last three centuries is filled with examples of animal species that were transformed into saleable commodities and then exploited to near-extinction. Between 1872 and 1874, an estimated 3,700,000 buffalo were slaughtered in the American West, of which only 150,000 were killed by the Plains Indians who traditionally hunted them.

In 1875 the commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, General Philip Sheridan opposed an attempt by the Texas legislature to conserve the remaining buffalo, on the grounds that white hunters had ‘done more in the last two years, and will do more in the next years, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last thirty years.’

For Sheridan, the extermination of the buffalo was a means of bringing about the extermination of the Indian population, and the only way ‘to bring lasting peace and allow civilisation to advance.’

In the early 21st century, the negative impact of ‘civilisation’ is now clearer than it was then, and species extinction is no longer regarded with the same equanimity - at least in theory. As humanity tries to come to terms with its unprecedented role as homo dominatus – the dominant species on earth, we have become painfully aware that nature may not be a ‘free gift’ after all, and that there are unforeseen consequences in regarding the natural world as an inexhaustible resource for the benefit of humanity,.

The Age of Extinction

Today we are in the midst of what scientists call the ‘Sixth Extinction’, in which more species are vanishing at a faster rate than the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs. We have been aware of this for a while now, though we have yet to act with the urgency required to mitigate and reverse the devastation.

In May 2019 a report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) – an international panel of more than 450 scientists from 109 nations – concluded that species loss has accelerated a rate of tens to hundreds of times faster than at anytime in the recent past.

Only this month the World Wildlife Fund for Nature’s (WWF) latest two-yearly Living Planet Index found an average decline of 69 percent in an analysis of 32,000 vertebrate populations since 1970, and that 2.5% of mammals, fish, reptiles, birds and amphibians have already gone extinct in the same period. This followed a previous rate of decline of 68 percent in the WWF’s 2020 report, and 60 percent in 2018.

In a year already mired in geopolitical chaos, and battered by apocalyptic possibilities, the report’s depiction of the depletion of global vertebrate wildlife as ‘code red for the planet (and for humanity)’ attracted a few headlines and then vanished into the ether.

Faced with rising energy bills, floods, droughts, and Putin’s threat to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, not many people wanted to consider the implications of an incredible 94 percent loss of diversity in Latin America since 1970, or the report’s conclusion that ‘humans use as many ecological resources as if we lived on almost two Earths.’

Like the depredations of Svalbard and the American West, the WWF attributed this decline to over-exploitation of species, particularly in the oceans, and also broader human activities, such as changes in land use, agricultural practices, deforestation, plastic pollution of the oceans, and over-use of water.

All this has brought us closer to what the sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson calls ‘the great loneliness’ - an era marked by an ‘existential and material isolation resulting from having extinguished so many other forms of life.’

As the WWF report points out, some of the negative consequences of this new age of extinction are already clear, including:

…the loss of lives and economic assets from extreme weather; aggravated poverty and food insecurity from droughts and floods; social unrest and increased migration flows; and zoonotic diseases that bring the whole world to its knees. Nature loss is now rarely perceived as a purely moral or ecological issue, with a broadened sense of its vital importance to our economy, social stability, individual well-being and health, and as a matter of justice.

Most of us will have heard variations on these ideas, but the report has particular resonance as the world struggles to move out of the pandemic, with the crucial 2022 UN Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, less than two months away.

In this context the WWF report is both a wake-up call and an invitation to imagine more hopeful futures, which seek to restore and reverse some of the damage of the last half-century

Such possibilities might seem a little distant right now, in a year in which the deforestation of the Amazon has reached record levels under the psychotic fascist Jair Bolsonaro, with more than 3, 980 square kilometres cleared in the first six months of 2022.

The WWF hails ‘Indigenous leadership’ - in other words the same ‘savages’ whose extermination Sheridan once advocated - in managing the planet’s depleted resources.

The report calls for a combination of Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge systems in bringing about a ‘just future’ which accesses both ‘mainstream’ and ‘Indigenous’ ways of knowledge and ways of knowing.

According to the NGO Global Witness, however, 200 land and environmental activists were killed worldwide in 2021 for trying to protect forests, animals and natural habitats, including eight rangers protected gorillas in the Virunga National Park of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Many of them were Indigenous land-rights activists, who are often at the cutting edge of capitalist over-exploitation. 78 percent of murdered activists came from the Amazon region, who were ‘being targeted by government, business and other non-state actors with violence, intimidation, smear campaigns and criminalisation. ‘

We should mourn their deaths, but also recognise the importance of what they tried to do, and what they wanted to protect.

Many years ago, the American naturalist Henry Beston called for ‘a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals’ based on the notion that ‘ They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the Earth.'

Pondering the future of the whaling industry, Herman Melville once wondered 'whether Leviathan can long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc; whether he must not at last be exterminated from the waters, and the last whale, like the last man, smoke his last pipe, and then himself evaporate in the final puff.'

Today, we are closer to that outcome that at any time in human history, in a speeded-up, technologised world in which achieving sustainability can often seem like trying to stop a runaway locomotive from crashing into the buffers.

But we haven’t crashed it yet. And if we want to make our governments do what we want them to do and prevent that outcome, we shouldn’t allow ourselves to be shocked into resigned passivity by the WWF’s report.

That’s not why its scientists compiled it, and the report’s aspirations for a ‘nature-positive’ society should remind us that we are part of nature, not separate from it, and invite us to imagine a different future in which things that are dying out can come back to life, and that we can thrive too if we accept our destiny as custodians of the planet which history, for better or worse, has placed in our hands.