In a decadent and intellectually-lazy country like the UK, every chest-beating pub bore and bilious expat columnist can rail against ‘human rights nonsense’, ‘woke human rights scams’, and other toxic variations on the same theme, and find a place on GB News or the Mail. Such pronouncements are almost always delivered in the context of ‘illegal’ immigration. Criticise the inane cruelty of UK immigration policy and you immediately define yourself as a paid up member of the human rights brigade.

Suggest that a ‘foreigner’ who has lived in the UK all his life, and has just been released from prison after serving a full sentence for GBH say, should not be deported to the country he was born in but has not seen since childhood, and these moral pundits will roll their eyes and shake their heads at yet another example of human rights gone mad.

Whatever the immediate cause, the core message is tediously familiar, ground out year after year, with the same weary knowing bitterness by the likes of Nigel Farage, Richard Littlejohn, and so many others.

It goes like this: you, the humble and hardworking, instinctively generous taxpaying British voter are being taken for a ride by slippery migrants who break our laws and then use European human rights legislation to protect themselves from the fate we all know they deserve - expulsion to the place they came from, or any other place our benign government wants to send them.

These devious infiltrators, backed up by an army of woke ‘lefty lawyers’ or ‘activist lawyers’ are preventing us from ‘protecting our borders’ through vexatious and politically-motivated appeals. All this is ‘human rights nonsense’, they cry, and it’s got to stop I tell you.

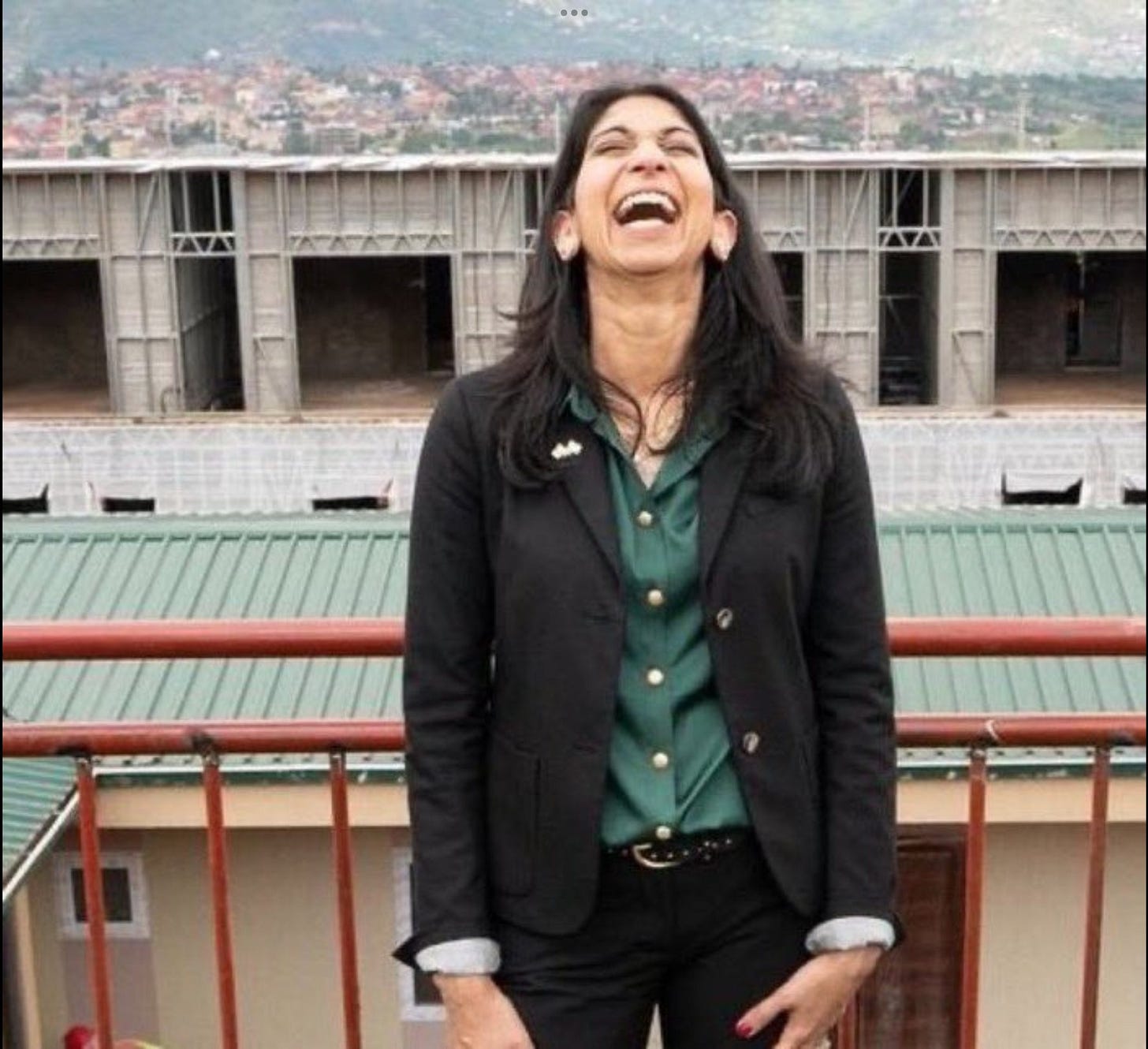

But now, hurrah! We finally have a government so contemptuous of the very concept of human rights that the Home Secretary is prepared to have herself photographed letting out an affected - or should it be infected - joyful laugh, while standing in front of a detention centre in Rwanda, in front of a carefully-picked selection of very rightwing journalist/courtiers who lap this kind of thing up.

I’ve often thought about that picture, travelling through Argentina these last few weeks, because this is a country where human rights really do matter. What human rights? you ask. Well the right not to be held without trial by the state security forces for one - or ‘held at the disposition of the national executive power’, as the 1976-83 military dictatorship used to put it, on the rare occasions when it admitted to holding anyone at all.

Then there is the right not to be ‘disappeared’ by the same security forces. Or the right not to be tortured. Or the right to a trial for whatever crimes one might have been accused of.

In Argentina, all these rights were massively violated by the military government that ruled the country from 1976-83, and you can’t go far without being reminded of these violations. Argentina is probably the only country in the world where you can find a barracks, with a large sign identifying it as a centre for clandestine detention, torture, and murder.

I saw this in the city of Neuquen, in northern Patagonia, and there are many other signs like it across the country, drawing attention to ‘little schools’ and detention centres where tens of thousands of people died at the hands of their own government, in addition to other monuments and ‘Spaces of Remembrance’ for the people who disappeared at the hands of the military.

In La Plata I saw faces of the high school students murdered by the military in September 1976 because they had the temerity to campaign against an increase in bus fares, painted on the walls of the local arts college.

In the central square in San Carlos de Bariloche, dozens of headscarves commemorating the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo are painted on the ground along with the names of victims of the dictatorship.

These memorials have been hard-won. The army barracks in Neuquén did not want a sign outside their base identifying their predecessors as murderers and torturers. The fact that such things can happen is the result of years of painstaking and relentless campaigning by Argentinian human rights activists, politicians, and municipal authorities, who have refused to allow the crimes of the dictatorship to be forgotten, and tried to use the memory of those crimes to ensure that the slogan ‘never again’ becomes firmly implanted in the collective memory of the Argentine people.

It’s thanks to these efforts that every year, on March 24, Argentina commemorates the victims of the dictatorship on the anniversary of the 1976 coup, with a public ‘Day of Remembrance for Truth and Justice’.

Argentina, as the writer Marcelo Valko told me, is very unjust country, but it’s also a country that understands the value of human rights, and has learned in the most horrific way what can happen when they are taken away, and when every citizen becomes the potential victim of a predatory state operating without legal accountability.

This is a country where men and women were kidnapped in the streets by security forces who never admitted that they were doing any such thing; where their relatives were also ‘disappeared’ if they demanded to know what had happened to their loved ones; where ‘activist’ and ‘lefty’ lawyers were secretly killed if they invoked habeus corpus who tried to uphold the laws that their own government was secretly breaking.

At the height of its power, the Argentine dictatorship also mocked ‘human rights nonsense’ with an World Cup sportswashing campaign that used the slogan ‘Somos Argentinos y somos derechos’ (‘We are Argentines and we are right’) to counter the condemnations of Argentina’s human rights violations from Amnesty International and other international organisations.

So Argentina’s acts of remembrance are intended to ensure that the past is not forgotten or misremembered, and they also shape the way Argentina responds to the persistent injustices in the present. In most large cities and small towns, posters and murals call for justice for murdered women and trans people; for Mapuche activists shot by the military; for the young ‘peon’ Daniel Solano, who was kidnapped and murdered by the police in the town of Choele Choel in 2013 because he denounced the financial malpractices of his employers.

The last testament of General Videla

Of course there are those who don’t want to remember the past in this way. Last week, in the run up to the Day of Remembrance, Twitter was awash with tweets praising the military dictatorship and downplaying its crimes, or listing the bombings and assassinations carried out by leftwing ‘urban guerrilla’ organisations in the 1970s in an attempt to establish a spurious moral equivalence between the state and its opponents.

Some of these accounts have the same kind of profiles you find in the US or the UK: pro-Trump, pro-Bolsonaro, patriots etc. But some of it comes from people who were alive during the dictatorship, and still regard the trials of its leading protagonists as a travesty.

Nor are these criticisms of ‘human rights nonsense’ merely a social media phenomenon. During the recent presidency of Mauricio Macri, leading Argentine human rights organisations criticised the desprecio - contempt - for their work emanating from state institutions such as the Supreme Court, which voted to reduce the sentence for a man convicted in 2013 for kidnap and torture during the dictatorship. In the first year of his presidency, Macri called the human rights policies of his predecessor Christina Kirchner a ‘scam.’

To some extent these ‘wars of remembering’ are a specifically Argentinian response to the horrors of its all-too-recent history. In an interview in prison shortly five years before his death in 2013, the former general Rafael Videla looked back without regret at the crimes committed by his regime. At one point he told his interviewer

Let’s suppose for the sake of argument that there were seven thousand and eight thousand people who had to die in order to win the war against subversion; we couldn’t shoot them. Nor could we bring them to justice.

If these people who ‘had to die’ but could not be shot, Videla’s argument implied, then it was perfectly logical and even essential for the state to kill them in secret. The figure that Videla gave was a gross and deliberate understatement, which was echoed by many of the pro-dictatorship tweeters last week. And his logic is equally fallacious and dishonest.

It is not for a handful of generals to decide who ‘has to die’ and then kill them their own citizens in secret. It is entirely disingenuous to equate the crimes carried out by urban guerrilla groups with the crimes of a state that wilfully and deviously abandons the rule of law in order to be able to murder its own citizens for their real or imagined political views.

To suggest that organizations like the Montoneros are as guilty of ‘human rights violations’ as the regime that set out to annihilate an entire political generation, is twisted sophistry and cynicism of the kind that the right tends to specialise in - in Argentina and in many other countries.

And this is where we come back to Suella Braverman’s performative chortle, because she represents a government for cynicism and cruelty come naturally, and not only through their sordid willingness to tickle the bellies of the worst people in the country in order to save their own wretched political skins. If I mention the likes of Sunak, Gullis and Braverman in the same breath as Videla, it isn’t because I place them on the same level of depravity as the murderous inquisitors who once terrorised Argentina.

But in seeking to remove their Rwanda policy from international legal scrutiny, Braverman and Sunak, like Videla and his cohorts, are constructing - whether they realise it or not - a class of people that has no rights and no institutions to protect them. The refugees who may be sent to Rwanda may not be the disappeared. They are not being tortured or killed. But their ‘removal’ to Rwanda will transform them into non-people, for whom no government bears responsibility, not the countries they fled from or the country they appealed to for safety, or the country where Braverman posed for a laugh in front of a detention centre.

In removing them from legal scrutiny and the possibility of legal representation, the Sunak government is attempting to strip them of will rights that took many years to develop and recognise, which they will not be able to recover. This is what Sunak and his gurning ‘populists’ are doing, though it’s a moot point whether they fully understand the full consequences of what they are doing.

In seeking to evade their own obligations, they are withdrawing the UK from a set of legal and moral obligations developed by the ‘international community’ - with the help of Conservative British governments - in the wake of World War II, in response to the dictatorships of the 1930s.

The more enlightened members of these democracies recognised the need for new internationally-recognised legislation that could be invoked to protect individuals from the arbitrary power of the state not just on the basis of political rights pertaining to national citizenship, but to broader rights associated with a common humanity that both included and transcended what individual states might do, and which could not be solely dependent on the whims of individual governments.

By binding governments to international agreements, the architects of this new human-rights era attempted to ensure that ‘never again’ became a guiding principle. This is why the UN agreed on a Universal Declaration of Human Right. It’s why we got the Geneva Convention on Refugees, and the European Convention on Human Rights, and the institutions that - at least in theory - uphold the rights and obligations contained in these agreements.

It’s true that some of the countries that signed these agreements have not always observed them in practice, particularly during the wars of decolonisation, and have sometimes ignored violations by allied states for reasons of political expediency. But the underlying principles that dictated the ‘human rights era’ still represented a qualitatively hopeful and aspirational turn in international relations, and in our common understanding of the relationship between individuals and their national governments, and individuals who find themselves subjected to arbitrary state power beyond their borders.

Such principles do not become obsolete simply because Lynton Crosby had advised a collapsing government to transform ‘stopping the boats’ into a hot button issue, or because the likes of Jonathan Gullis and Lee Anderson want to save their seats. Yet here we are, in the swamp and sinking into it. And the fact that one of the leading architects of this new era is now walking away from the rights it once helped define, while chortling for clicks in front of the likes of GB News, is a testament to its ignorance as well as its moral vacuity.

And even if Braverman may not be Videla or Maseera, she is in its own way, an obscenity, whose stupidity and cruelty has received praise from fascist and extreme-right parties across Europe.

They don’t like this ‘human rights nonsense’ any more than the Argentine right does, or the likes of Richard Littlejohn and Jacob Rees-Mogg do. And the more they condemn it, the more it behoves all of us - left, right, and centre - who still believe in the universal principles that the post-war era once defined, to oppose these insidious attempts to lead the world into a new dark age, in a time when human rights are as essential as they were when they were first agreed upon.

And in the latest instalment of “Stuff Even Littlejohn Wouldn’t Make Up” the Daily Heil has invoked human rights legislation to prevent the naming of 73 journalists involved in the legal action re phone-hacking.