History doesn’t owe any country anything, and only very foolish or complacent societies think that are somehow immune to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune that might be fired in their direction, at any time, and from anywhere.

For a long time the UK has been one of those countries. Lulled into a false sense of security by a long period in which we were not expected to do very much except go shopping and watch our house prices go up, we have forgotten how easily the stability that we take for granted can fall apart. Admittedly we haven’t helped by a succession of governments that have looked down at the country from a great height, without really caring that much about the little people milling around beneath them.

But now it is difficult to ignore the distinct roaring of the rapids that the country is drifting towards, with the dreamy insouciance of Jerome K. Jerome’s three men in a boat.

This week, for example, we learned that the energy bills are set to rise to £3,582 a year - an announcement that will be made at the end of the month, and will take effect in October. By January, according to the well-regarded consultancy firm Cornwall Insight, the average household bill will reach an incredible £4,266 a year.

Everyone knows that millions of households will not be able to pay these bills, or their rents or mortgages, and that millions will slip into poverty and will not be able to cook or heat their homes, without making stark choices between staying warm and feeding their families.

I repeat: millions of people. And even those who can afford to pay will have to make drastic cuts to their household budgets, at a time when food prices are rising and inflation is eating into salaries that have not risen in years, and many working people are already struggling to make ends meet.

What will happen when these increases begin to bite? What, apart from a few hundred pounds here and there, is the government offering to help the people who will be most affected by them? Why is the government allowing this calamity to unfold? Why is the opposition not shouting from the rooftops that these outcomes are unsustainable and cannot be allowed to stand?

The answers appear to be blowing in the wind. This week, a leaked report revealed that the government is preparing for what the Huffington Post called ‘1970s-style organised blackouts’ in both households and industries, in the event of gas and electricity shortages.

On one hand, we should be grateful that the somnolent UK government has roused itself from its stupor to prepare for anything at all, but this outcome is not something to look forward to, regardless of the government’s assurance that it is ‘not something we expect to happen’ and that ‘ Households, businesses and industry can be confident they will get the electricity and gas they need.’

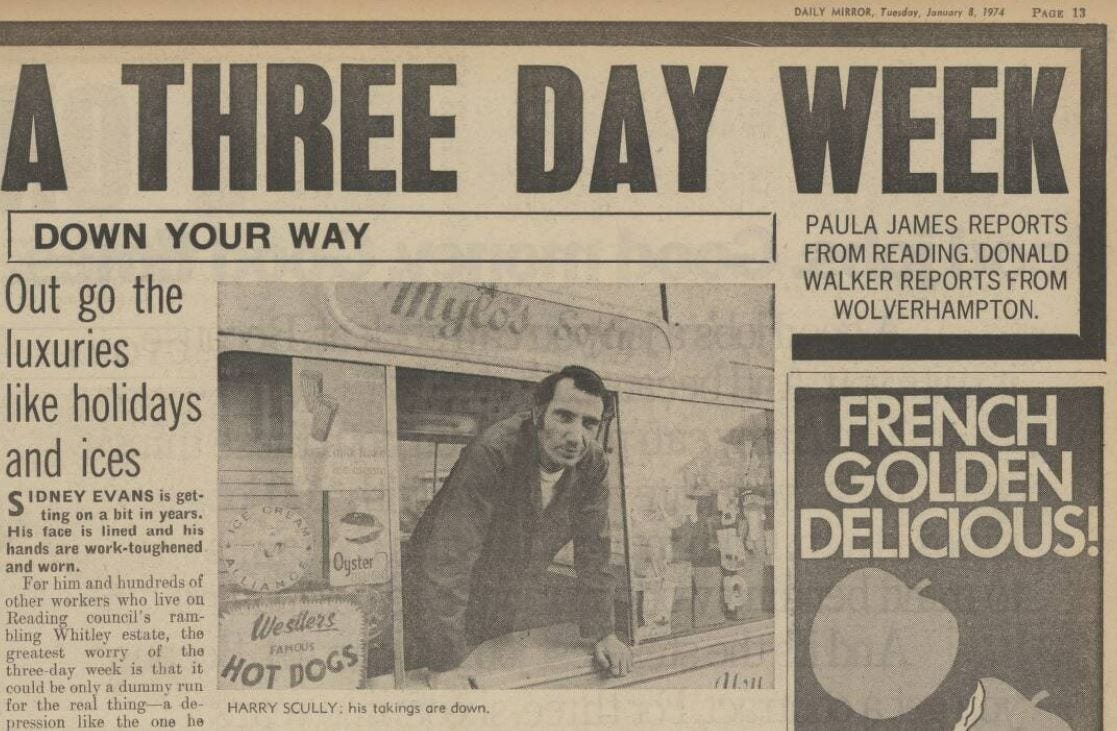

As someone who lived through those ‘1970s-style’ blackouts during the 1973-74 three-day week, I have only vague memories of the tv suddenly going off and the house plunged into darkness. I was too young to fully understand the ongoing conflict between the miners and the Heath government, or the implications of the October 1973 Yom Kippur war, and the OPEC oil embargo which led to a quadrupling of oil prices.

I wasn’t aware of Ted Heath’s minister for energy Patrick Jenkin, who advised the public to brush their teeth in the dark to save electricity, only have his house photographed a few days later showing the ‘lights on in five windows.’

In his excellent account of Britain in the seventies When the Lights Went Out, Andy Beckett argues that the Heath government’s declaration of a three-day week in December 1973 was a political as well as an economic decision, intended to shock the National Union of Mineworkers - and the public - into accepting the Tory government’s wage restraint policies.

These were the days - long gone - when British governments negotiated directly with trade unions behind closed doors. In the case of the miners, Heath’s government failed to answer the question put to it during these negotiations ‘Why can’t you pay us for coal what you are willing to pay the Arabs for oil?’

On 13 December Heath made a special prime-ministerial broadcast to announce the ‘grave emergency’ the nation faced, and the restrictions his government intended to impose in order to conserve fuel stocks:

I know that the new restrictions will make life very much harder for all of us…We shall have a harder Christmas than we have had since the war…We shall have to postpone some of the hopes and aims we have set ourselves for expansion and for our standard of living.

Nevertheless

At times like these, there is deep in all of us an instinct which tells us that we must abandon disputes amongst ourselves. We must close our ranks, so that we can deal together with the difficulties which come to us, whether from within or from beyond our shores…Our future and the character of the country depend on it.

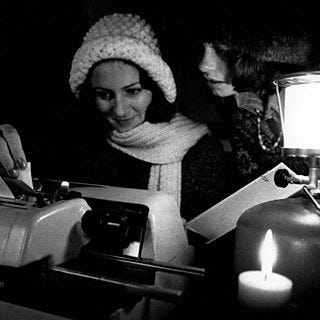

Heath’s appeal to national unity failed. In January 1974 the NUM rejected the government’s 16. 5 percent pay rise and voted to strike. For more than two months, the country followed the restrictions. Television shut down at 10.30. Shopkeepers served their customers by candlelight. Office workers wrapped themselves in quilts, and petrol stations ran out of fuel.

Who Governs? No one

On 28 February 1973, Heath called a snap election, asking the question ‘Who governs?’ - meaning the unions or his government. A hung parliament failed to answer this question, prompting another election that autumn, which Labour narrowly won.

At that time, memories of the war and rationing were still recent enough for the British public to more or less take Heath’s ‘grave emergency’ in its stride, even if voters ultimately rejected the government that declared it.

It is difficult to imagine such equanimity today.

Some of the ingredients in the current crisis may echo the 1973-74 crisis - the impact of a foreign war on energy prices; a mild union resurgence after years in which trade union power has been a negligible factor in UK politics - but the country is in a very different, and in some ways, much more perilous position that it was back then.

If the question ‘who governs’ was asked right now, the answer would not be the trade unions, nor would it be the government. Apart from a brief period in the pandemic, when Boris Johnson and his Brexit cabal were dragged kicking and screaming into behaving like an interventionist government, this is an administration hollowed out of talent and principle by an ethnonationalist Brexit fantasy that has yet to land in the real world.

This is a government that even when it seemed to function was often more concerned with saving face and inventing day-to-day distractions and deflections than in actually governing the country for the benefit of its population.

Its members make Heath and his cabinet seem like dedicated public servants, which in many ways they were. Now, at precisely the time when we need urgent action to mitigate the calamity that we are heading towards, the government is effectively AWOL, regardless of the fact that Bertie Booster took time off from his holiday to reassure the public that he is ‘absolutely certain’ the next PM will take action to protect the public.

Nothing that the two leadership contenders have said gives any indication that they understand the magnitude of what is about to happen, or even that they particularly care about it. The insufferable Liz Truss gazes into the horizon for a succession of ‘leadership’ photo ops, while rejecting ‘handouts’ in favour of tax cuts that will have little or no impact on the majority of the people who will bear the brunt of the coming crisis.

Sunak may be more economically literate, but a politician who brags about diverting cash from deprived areas to Tunbridge Wells is not the man you go to seek a limit on energy price caps or subsidise energy companies to make sure that wholesale costs are not passed onto the customer.

Nor, at the moment, is there much sign of life from the opposition, despite the open goals opening up in front of it.

So this is not the 1970s. It is Britain 2022 - a country in which the basic nuts and bolts that hold society together have been systematically unfastened, largely as a result of twelve dire years of Tory austerity followed by Tory Brexit followed by the worst government in British history.

It’s a country where you are lucky to even get a GP appointment; where you can’t even see a dentist as an NHS patient unless you already go to a practice; where the NHS is buckling under the strain of successive crises; where a drought is now unfolding while water companies pour sewage into rivers and waste 2.4 billion litres a day; where Brexit has caused supply chain disruptions and labour shortages and an array of bureaucratic problems for businesses that British politicians are too cowardly even to acknowledge.

This is where we are after years of misgovernance, of deregulation and privatisation, of corporate greed and corporate irresponsibility, all waved through by a feckless ruling class that has now succumbed to the destructive fanaticism and wishful thinking of the Brexit project.

In other words this is a country whose reserves of resilience have run dangerously low, and we haven’t even seen the worst of the ‘cost-of-living’ crisis yet.

So the rumours of ‘civil unrest’ are probably not unfounded. The Sun once warned of ‘chaos not seen since the 1970s’ if Jeremy Corbyn was elected.

The chaos that we have witnesses these last few years has nothing to do with Corbyn or Labour. It is Tory chaos and Tory misery, and as we face a winter of converging crises, civil unrest may be essential if we are to rid ourselves of the party that has inflicted so much damage on the country it claims to love.

Because sometimes there is no other way to get a bad government to behave better, and no other way to get rid of a bad government, and no other way to rouse an opposition to take the urgent action required to protect the public from the incoming disasters that millions of people simply will not be able to cope with.

Sorted Ian. Thanks

Very good piece - a couple of typos, you have £3,582 a month and £4,266 a month when you mean "a year".