In the late 19th century, Victorian-era scientists concocted and propagated a worldview in which ‘weaker’ or ‘inferior’ races were seen as the inevitable collateral damage of progress and modernity. Geologist, ethnologists, naturalists, and anthropologists all reinforced the morbid fatalism of these ‘dark vanishings’, as Patrick Brantlinger called them, in which ‘savage’ peoples were seen as predestined for extinction as a consequence of their inability to adapt to modern civilisation. Such disappearances might be lamented - up to a limited point - but more importantly, there were to be recorded and studied.

The more likely it was that a particular people was headed for extinction, the more valuable such peoples became as ethnological and anthropological ‘data’, or as pieces in a human origins puzzle that attempted to show lines of progress from ‘primitive’ to ‘civilised’ man, with the latter inevitably by occupied Europeans and their descendants. As European settlers and colonists pushed out into ‘empty’ lands across the globe, scientists and travellers followed in their wake, collating information about the customs, languages, and way of life of the peoples who were being marginalised, conquered, and displaced.

Some gathered physical ‘evidence’ of these disappearances, in the form of skulls and skeletons that could be studied and measured to prove this or that thesis, or exhibited in museums or personal collections as scientific trophies, whose value was increased by their rarity or their proximity to extinction. In some cases, human remains were robbed from indigenous tombs and burial grounds, or taken directly from the sites of battles and massacres.

These tendencies reached an apotheosis of morbidity in Argentina, with the inauguration of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales (Museum of Natural Sciences) in La Plata in 1888. The museum was the brainchild of the well-connected Argentine naturalist and explorer Francisco ‘Perito’ (Clever or Learned) Moreno (1852-1919). An avid collector of paleontological animal and human objects since childhood, Moreno also took a keen and even obsessive interest in collecting the more recent remains of the indigenous peoples in his own country.

By the time construction on the La Plata museum began in 1881, Moreno had already acquired a huge collection of indigenous skulls and skeletal remains during his travels across the Pampas and Patagonia. Moreno was a peculiar character, who befriended Indians and sometimes sympathised with them, yet also fully embraced the extinction narratives of his peers in Argentina and abroad.

Even though some of his expeditions were made possible through safe conduct passes obtained from Indian caciques (chiefs), Moreno had no compunction about stealing the remains of people from Indian burial grounds, some of whom he had known when they were alive, and he sometimes seemed to be waiting for living people to die so that he could make off with their remains.

Moreno found no shortage of skulls and skeletons, at a time when the Patagonian and Pampean Indians were being decimated by smallpox and the southwards advance of the Argentinian military. Here, as was often the case in other countries, ‘extinction’ overlapped with ‘extermination’, as the Argentine armed forces cleared the Patagonian ‘desert’ for settlement by European immigrants and farmers.

At times, it’s difficult to determine whether Moreno’s motivation in acquiring these human remains was scientific or patriotic - insofar as science was seen as a means of acquiring national prestige for his country - or whether they were intended to advance his own personal reputation. Some Indian communities were aware of his interests and regarded him as a ghoul or malign spirit, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that they had a point.

Whatever his intentions, Moreno’s collection formed the basis of the museum’s exhibits when it was inaugurated in 1888. In addition to paleontological fauna, megatherium, dinosaurs and the like, the museum displayed the skulls and skeletons of Indians in glass showcases, who had died or been killed, with the names of high-profile caciques who Moreno regarded as notable trophies/exhibits.

In a grotesque twist on the extinction discourse of the period, Moreno even kept living Indians as exhibits, who lived in the basement of the museum. At least fifteen people were kept there, under Moreno’s aegis. Some of them helped clean the building or contributed to its construction. Others were expected to appear in public, weaving or sewing, in a variation of the ‘human zoos’ that were so popular in Europe at the time.

These Indians were painted and photographed. An Italian-Argentine sculptor took bronze casts of their heads. Some of them posed as subjects for the romanticised murals on the museum walls which show Indians living a life that their compatriots in the museum could no longer live, as a result of the Argentine army’s ‘Conquest of the Desert.’

‘Living exhibits’

It is difficult to imagine what these ‘living exhibits’ must have felt living in these conditions. Bear in mind that most of them arrived at the museum as prisoners of war. Some had witnessed the violent destruction of their camps and settlements, the loss of their homes and the separation of their families. Others, like the cacique Inacayal, had been plucked from ‘deposits of Indians’ - essentially, concentration camps, and brought by Moreno to the museum:

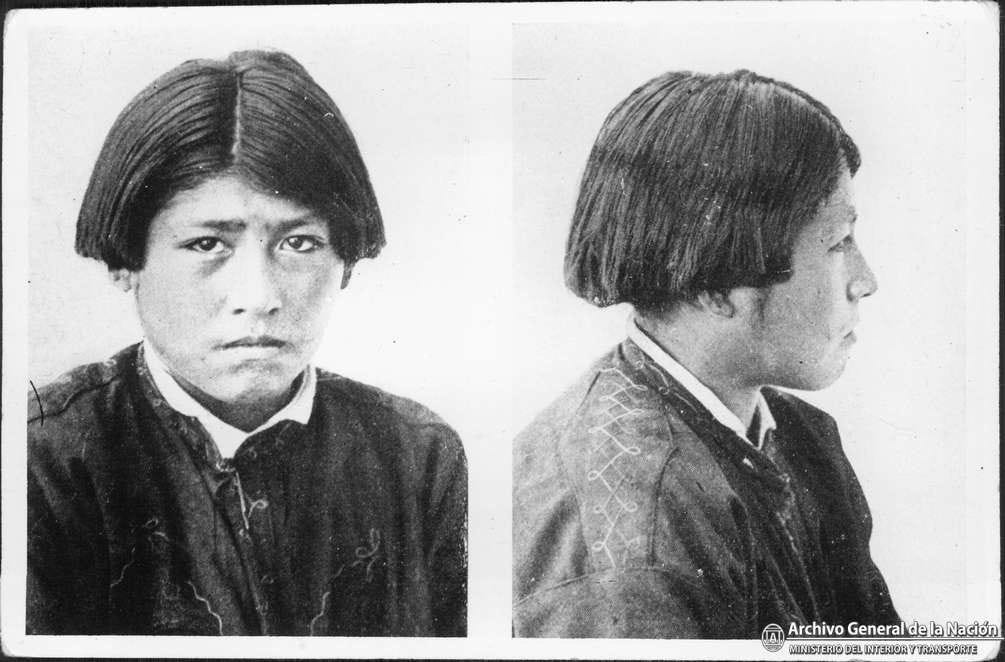

Inacayal, according to a Dutch anthropologist who worked at the museum at the time, was prone to angry rants about the lands and horses he had lost to the ‘huinca’ - white man. Other residents of the museum have left no written record of their time there, only their photographs, often accompanied by Bertillonage-style profiles which emphasise both their alien ‘otherness’ and their value as ‘data’ - the ‘last’ relics of indigenous Argentina vanquished on the battlefield and doomed to be replaced by waves of European immigration.

A few did manage to return to the lands they had been taken from. But others died in the museum basement, and their flesh was stripped from their bodies to provide new exhibits for Moreno’s display cabinets. When Inacayal died in 1888, his body was dissected, and various parts put on display.

Today the science that once stripped these men and women of their humanity and personhood has changed, and so have the political and cultural expectations from which these procedures emerged.

Since the early 1990s, the indigenous remains at La Plata have become the object of a powerful campaign for restitution, whose protagonists include the communities these men and women came from, anthropologists from the La Plata university, and human rights activists, all of whom reject the racial hierarchies that prevailed in Moreno’s time.

In 1994 the skull and bones of Inacayal were returned to his ancestral lands in the Patagonian province of Chubut, and given a ceremonial Mapuche burial. In 2014, his brain was returned to Chubut, together with other body parts and a poncho which he once gave to Moreno, following the 2006 National Law 25.517, which mandates the return of indigenous remains to the communities they came from.

Other restitutions have been completed, or remain pending. I went to the museum to discuss these processes with the museum director Dr Analia Lanteri and the head of Anthropology Dr Gustavo Barrientos.

The museum itself is an incredible and imposing sight even today, with its great stone lions and neo-classical columns, and one can only imagine how it must have appeared in the late 19th century when La Plata barely existed. From the outside it looks like a temple, which is undoubtedly how Moreno and his fellow-Darwinians intended it. Inside it is equally impressive, from the bust of Moreno himself, which greets the visitor, against the background of the Indians he believed to be on the brink of extinction:

Or the awesome exhibits themselves, plucked from the Argentinian necropolis which once fascinated Darwin:

Today the displays of human skulls and skeletons that once accompanied these exhibits have long gone, and the museum’s ethnological section stresses cultural diversity, respect and survival in its indigenous exhibits. But the process of restitution raises all kinds of questions that I wanted to answer. What are the logistics involved? Who instigates the process of restitution? What are the legal norms through which this procedures are carried out? What takes precedence when new remains are found - science or the needs of communities? How has a museum with such a grim history adapted itself to the new ethical challenges of the 21st century and a new understanding of Argentina’s Pueblos Originarios (First Peoples).

These were some of the issues I discussed with Doctor Lanteri and Doctor Barrientos. Afterwards, I was allowed to see the basement where Inacayal and his fellow ‘prisoners of science’ lived out their last years.

I was shown the room where other indigenous remains are kept while awaiting decisions regarding their restitution. The restitution cases are kept in boxes with their names inscribed. They include the skull of Calfucurá, the ‘Napoleon of the Pampas’, which various indigenous communities have laid claim to, even though the museum’s scientists believe the skull belongs to someone much younger than he would have been.

It was an extraordinary moment, to see the names of caciques and Indians who I was already familiar with, on white boxes lined up on shelves in the basement where some of them had died, waiting to be returned to the places they came from. But the presence on those shelves also gives the lie to the expectations of Moreno and his peers. They are going back to their ancestral lands because their communities survived, and want them back.

In seeking to give them the dignity and the personhood that was once taken from them in the past, these communities are also looking for the respect, equality and humanity in the present that Moreno and his contemporaries were unable or unwilling to recognise. Clearly Argentina has changed, and science has changed too, but in a world where First Peoples from the Arctic to Tierra del Fuego are still fighting for recognition and survival, it is salutary to recall this dark and often forgotten chapter in the history of white supremacy, when scientists collected the remains of ‘savages’ as evidence of their inferiority and their imminent disappearance, and extinction was often a euphemism for extermination